United States Agency for International Development

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. The reason given is: MOS:LEADREL. (February 2025) |

Seal of USAID | |

Flag of USAID | |

Wordmark of USAID | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | November 3, 1961 |

| Preceding agency | |

| Headquarters | Ronald Reagan Building Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Motto | "From the American people" |

| Employees | 10,235 employees (FY 2016)[1] |

| Annual budget | $50 billion (FY 2023 Budgetary Resources) |

| Agency executive |

|

| Website | www |

| Footnotes | |

| [2] | |

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is an independent agency of the United States government that is primarily responsible for administering civilian foreign aid and development assistance. With a budget of over $50 billion,[4] USAID is one of the largest official aid agencies in the world and accounts for more than half of all U.S. foreign assistance – the highest in the world in absolute dollar terms. USAID has missions in over 100 countries, primarily in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe.

Among the many positive accomplishments by USAID over the course of its history was to help bring an end to apartheid in South Africa through peaceful means.[5]

In 2025, the second Trump administration announced sweeping changes to USAID. President Donald Trump ordered a near-total freeze on all foreign aid.[6][7] Elon Musk, director of the Department of Government Efficiency, announced the intention of shutting down USAID.[8]

Creation

Congress passed the Foreign Assistance Act on September 4, 1961, which reorganized U.S. foreign assistance programs and mandated the creation of an agency to administer economic aid. USAID was subsequently established by the executive order of President John F. Kennedy, who sought to unite several existing foreign assistance organizations and programs under one agency.[9] USAID became the first U.S. foreign assistance organization whose primary focus was long-term socioeconomic development.

Congress authorizes USAID's programs in the Foreign Assistance Act,[10] which Congress supplements through directions in annual funding appropriation acts and other legislation. As an official component of U.S. foreign policy, USAID operates subject to the guidance of the president, secretary of state, and the National Security Council.[11]

Purposes

USAID's decentralized network of resident field missions is drawn on to manage U.S. government programs in low-income countries for various purposes.[12]

- Disaster relief

- Poverty relief

- Technical cooperation on global issues, including the environment

- U.S. bilateral interests

- Socioeconomic development

Disaster relief

Some of the U.S. government's earliest foreign aid programs provided relief in war-created crises. In 1915, U.S. government assistance through the Commission for Relief in Belgium headed by Herbert Hoover prevented starvation in Belgium after the German invasion. After 1945, the European Recovery Program championed by Secretary of State George Marshall (the "Marshall Plan") helped rebuild war-torn Western Europe.

USAID manages relief efforts after wars and natural disasters through its Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance, which is the lead federal coordinator for international disaster assistance.

Poverty relief

After 1945, many newly independent countries needed assistance to relieve the chronic deprivation afflicting their low-income populations. USAID and its predecessor agencies have continuously provided poverty relief in many forms, including assistance to public health and education services targeted at the poorest. USAID has also helped manage food aid provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Also, USAID provides funding to NGOs to supplement private donations in relieving chronic poverty.

Global issues

Technical cooperation between nations is essential for addressing a range of cross-border concerns like communicable diseases, environmental issues, trade and investment cooperation, safety standards for traded products, money laundering, and so forth. The United States has specialized federal agencies dealing with such areas, such as the Centers for Disease Control and the Environmental Protection Agency. USAID's special ability to administer programs in low-income countries supports these and other U.S. government agencies' international work on global concerns.

Environment

Among these global interests, environmental issues attract high attention. USAID assists projects that conserve and protect threatened land, water, forests, and wildlife. USAID also assists projects in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and building resilience to the risks associated with global climate change.[13] U.S. environmental regulation laws require that programs sponsored by USAID should be both economically and environmentally sustainable.

U.S. national interests

Congress appropriates exceptional financial assistance to allies to support U.S. geopolitical interests, mainly in the form of "Economic Support Funds" (ESF). USAID is called on to administer the bulk (90%) of ESF[14] and is instructed: "To the maximum extent feasible, [to] provide [ESF] assistance ... consistent with the policy directions, purposes, and programs of [development assistance]."[15]

Also, when U.S. troops are in the field, USAID can supplement the "Civil Affairs" programs that the U.S. military conducts to win the friendship of local populations. In these circumstances, USAID may be directed by specially appointed diplomatic officials of the State Department, as has been done in Afghanistan and Pakistan during operations against al-Qaeda.[16]

U.S. commercial interests are served by U.S. law's requirement that most goods and services financed by USAID must be sourced from U.S. vendors.[17]

Socioeconomic development

To help low-income nations achieve self-sustaining socioeconomic development, USAID assists them in improving the management of their own resources. USAID's assistance for socioeconomic development mainly provides technical advice, training, scholarships, commodities, and financial assistance. Through grants and contracts, USAID mobilizes the technical resources of the private sector and other U.S. government agencies, universities, and NGOs to participate in this assistance.

Programs of the various types above frequently reinforce one another. For example, the Foreign Assistance Act requires USAID to use funds appropriated for geopolitical purposes ("Economic Support Funds") to support socioeconomic development to the maximum extent possible.

Modes of assistance

USAID delivers both technical assistance and financial assistance.[18]

Technical assistance

Technical assistance includes technical advice, training, scholarships, construction, and commodities. USAID contracts or procures technical assistance and provides it in-kind to recipients. For technical advisory services, USAID draws on experts from the private sector, mainly from the assisted country's pool of expertise and from specialized U.S. government agencies. Many host-government leaders have drawn on USAID's technical assistance to develop IT systems and procure computer hardware to strengthen their institutions.

To build indigenous expertise and leadership, USAID finances scholarships to U.S. universities and assists in the strengthening of developing countries' universities. Local universities' programs in developmentally important sectors are assisted directly and through USAID support for forming partnerships with U.S. universities.

The various forms of technical assistance are frequently coordinated as capacity-building packages for the development of local institutions.

Financial assistance

Financial assistance supplies cash to developing country organizations to supplement their budgets. USAID also provides financial assistance to local and international NGOs who in turn give technical assistance in developing countries. Although USAID formerly provided loans, all financial assistance is now provided in the form of non-reimbursable grants.

In recent years, the United States has increased its emphasis on financial rather than technical assistance. In 2004, the Bush administration created the Millennium Challenge Corporation as a new foreign aid agency that is mainly restricted to providing financial assistance. In 2009, the Obama administration initiated a major realignment of USAID's own programs to emphasize financial assistance, referring to it as "government-to-government" or "G2G" assistance.

Public–private partnerships

In April 2023, USAID and the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) announced a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to improve food safety and sustainable food systems in Africa.[19] GFSI's work in benchmarking and standard harmonisation aims to foster mutual acceptance of GFSI-recognized certification programmes for the food industry.

Organization

USAID is organized around country development programs managed by resident USAID offices in developing countries ("USAID missions"), supported by USAID's global headquarters in Washington, DC.[20]

Country development programs

USAID plans its work in each country around an individual country development program managed by a resident office called a "mission". The USAID mission and its U.S. staff are guests in the country, with a status that is usually defined by a "framework bilateral agreement" between the government of the United States and the host government.[21] Framework bilaterals give the mission and its U.S. staff privileges similar to (but not necessarily the same as) those accorded to the U.S. embassy and diplomats by the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961.[22]

USAID missions work in over fifty countries, consulting with their governments and non-governmental organizations to identify programs that will receive USAID's assistance. As part of this process, USAID missions conduct socio-economic analysis, discuss projects with host-country leaders, design assistance to those projects, award contracts and grants, administer assistance (including evaluation and reporting), and manage flows of funds.[23]

As countries develop and need less assistance, USAID shrinks and ultimately closes its resident missions. USAID has closed missions in a number of countries that had achieved a substantial level of prosperity, including South Korea,[24] Turkey,[25] and Costa Rica.

USAID also closes missions when requested by host countries for political reasons. In September 2012, the U.S. closed USAID/Russia at that country's request. Its mission in Moscow had been in operation for two decades.[26] On May 1, 2013, the president of Bolivia, Evo Morales, asked USAID to close its mission, which had worked in the country for 49 years.[27] The closure was completed on September 20, 2013.

USAID missions are led by mission directors and are staffed both by USAID Foreign Service officers and by development professionals from the country itself, with the host-country professionals forming the majority of the staff. The length of a Foreign service officer's "tour" in most countries is four years, to provide enough time to develop in-depth knowledge about the country. (Shorter tours of one or two years are usual in countries of exceptional hardship or danger.)[28]

The mission director is a member of the U.S. Embassy's "Country Team" under the direction of the U.S. ambassador.[29] As a USAID mission works in an unclassified environment with relative frequent public interaction, most missions were initially located in independent offices in the business districts of capital cities. Since the passage of the Foreign Affairs Agencies Consolidation Act in 1998 and the bombings of U.S. Embassy chanceries in east Africa in the same year, missions have gradually been moved into U.S. Embassy chancery compounds.

USAID/Washington

The country programs are supported by USAID's headquarters in Washington, D.C., "USAID/Washington", where about half of USAID's Foreign Service officers work on rotation from foreign assignments, alongside USAID's Civil Service staff and top leadership.

USAID is headed by an administrator. Under the Biden administration, the administrator became a regular attendee of the National Security Council.

USAID/Washington[30] helps define overall federal civilian foreign assistance policy and budgets, working with the State Department, Congress, and other U.S. government agencies. It is organized into "Bureaus" covering geographical areas, development subject areas, and administrative functions. Each bureau is headed by an assistant administrator appointed by the president.

(Some tasks similar to those of USAID's Bureaus are performed by what are termed "Independent Offices".)

- Geographic bureaus

- AFR – Africa

- ASIA – Asia

- LAC – Latin America & the Caribbean

- E&E – Europe and Eurasia

- ME – the Middle East

- Subject-area bureaus

- GH – Global Health

- Every year, the Global Health Bureau reports to the U.S. Congress through its Global Health Report to Congress.[31] The Global Health Bureau also submits a yearly report on the Call to Action: ending preventable child and maternal deaths.[32] This is part of USAID's follow-up to the 2012,[33] where it committed to ending preventable child and maternal deaths in a generation with A Promise Renewed.[34]

- E3 – Economic Growth, Education, and the Environment

- Economic Growth offices in E3 define Agency policy and provide technical support to Mission assistance activities in the areas of economic policy formulation, international trade, sectoral regulation, capital markets, microfinance, energy, infrastructure, land tenure, urban planning and property rights, gender equality and women's empowerment. The Engineering Division, in particular, draws on licensed professional engineers to support USAID Missions in a multibillion-dollar portfolio of construction projects, including medical facilities, schools, universities, roads, power plants, and water and sanitation plants.

- The Education Office in E3 defines Agency policy and provides technical support to Mission assistance activities for both basic and tertiary education.

- Environment offices in E3 define Agency policy and provide technical support to Mission assistance activities in the areas of climate change and biodiversity.

- Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance

- Bureau for Democracy, Human Rights and Governance

- LAB – U.S. Global Development Lab

- The Lab serves as an innovation hub, taking smart risks to test new ideas and partner within the Agency and with other actors to harness the power of innovative tools and approaches that accelerate development impact.[37]

- RFS – Resilience and Food Security

- GH – Global Health

- Headquarters bureaus

- M – Management

- OHCTM – Office of Human Capital and Talent Management

- LPA – Legislative and Public Affairs

- PPL – Policy, Planning, and Learning

- BRM – Office of Budget and Resource Management

Independent oversight of USAID activities is provided by its Office of Inspector General, U.S. Agency for International Development, which conducts criminal and civil investigations, financial and performance audits, reviews, and inspections of USAID activities around the world.

Staffing

USAID's staffing reported to Congress in June 2016 totaled 10,235, including both field missions "overseas" (7,176) and the Washington DC headquarters (3,059).[38]

Of this total, 1,850 were USAID Foreign Service officers who spend their careers mostly residing overseas (1,586 overseas in June 2016) and partly on rotation in Washington DC (264). The Foreign Service officers stationed overseas worked alongside the 4,935 local staff of USAID's field missions.

Host-country staff normally work under one-year contracts that are renewed annually.[39] Formerly, host-country staff could be recruited as "direct hires" in career positions[40] and at present many host-country staff continue working with USAID missions for full careers on a series of one-year contracts. In USAID's management approach, local staff may fill highly responsible, professional roles in program design and management.[41]

U.S. citizens can apply to become USAID Foreign Service officers by competing for specific job openings based on academic qualifications and experience in development programs.[42] Within five years of recruitment, most Foreign Service officers receive tenure for an additional 20+ years of employment before mandatory retirement. Some are promoted to the Senior Foreign Service with extended tenure, subject to the Foreign Service's mandatory retirement age of 65.

(This recruitment system differs from the State Department's use of the "Foreign Service Officer Test" to identify potential U.S. diplomats. Individuals who pass the test become candidates for the State Department's selection process, which emphasizes personal qualities in thirteen dimensions such as "Composure" and "Resourcefulness". No specific education level is required.[43])

In 2008, USAID launched the "Development Leadership Initiative" to reverse the decline in USAID's Foreign service officer staffing, which had fallen to a total of about 1,200 worldwide.[44] Although USAID's goal was to double the number of Foreign Service officers to about 2,400 in 2012, actual recruitment net of attrition reached only 820 by the end of 2012. USAID's 2016 total of 1,850 Foreign Service officers compared with 13,000 in the State Department.[45]

Field missions

While USAID can have as little presence in a country as a single person assigned to the U.S. Embassy, a full USAID mission in a larger country may have twenty or more USAID Foreign Service officers and a hundred or more professional and administrative employees from the country itself.

The USAID mission's staff is divided into specialized offices in three groups: (1) assistance management offices; (2) the mission director's and the Program office; and (3) the contracting, financial management, and facilities offices.[46]

Assistance management offices

Called "technical" offices by USAID staff, these offices design and manage the technical and financial assistance that USAID provides to their local counterparts' projects. The technical offices that are frequently found in USAID missions include Health and Family Planning, Education, Environment, Democracy, and Economic Growth.

Health and Family Planning

Examples of projects assisted by missions' Health and Family Planning offices are projects for the eradication of communicable diseases, strengthening of public health systems focusing on maternal-child health including family planning services, HIV-AIDS monitoring, delivery of medical supplies including contraceptives, and coordination of Demographic and Health Surveys. This assistance is primarily targeted to the poor majority of the population and corresponds to USAID's poverty relief objective, as well as strengthening the basis for socio-economic development.

Education

USAID's Education offices mainly assist the national school system, emphasizing broadening the coverage of quality basic education to reach the entire population. Examples of projects often assisted[citation needed] by Education offices are projects for curriculum development, teacher training, and provision of improved textbooks and materials. Larger programs have included school construction. Education offices often manage scholarship programs for training in the U.S., while assistance to the country's universities and professional education institutions may be provided by Economic Growth and Health offices. The Education office's emphasis on school access for the poor majority of the population corresponds to USAID's poverty relief objective, as well as to the socioeconomic development objective in the long term.

Environment

Examples of projects assisted by environmental offices are projects for tropical forest conservation, protection of indigenous people's lands, regulation of marine fishing industries, pollution control, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, and helping communities adapt to climate change. Environment assistance corresponds to USAID's objective of technical cooperation on global issues, as well as laying a sustainable basis for USAID's socioeconomic development objective in the long term.

USAID (United States Agency for International Development) has recently initiated the HEARTH (Health, Ecosystems and Agriculture for Resilient, Thriving Societies) program, which operates in 10 countries with 15 activities aimed at promoting conservation of threatened landscapes and enhancing community well-being by partnering with the private sector to align business goals with development objectives. Through HEARTH, USAID implements One Health principles to achieve sustainable benefits for both people and the environment through projects focused on livelihoods, well-being, conservation, biodiversity, and governance.[47]

Democracy

Examples of projects assisted by Democracy offices are projects for the country's political institutions, including elections, political parties, legislatures, and human rights organizations. Counterparts include the judicial sector and civil society organizations that monitor government performance. Democracy assistance received its greatest impetus at the time of the creation of the successor states to the USSR starting in about 1990, corresponding both to USAID's objective of supporting U.S. bilateral interests and to USAID's socioeconomic development objective.

Economic Growth

Examples of projects often assisted by Economic Growth offices are projects for improvements in agricultural techniques and marketing (the mission may have a specialized "Agriculture" office), development of microfinance industries, streamlining of Customs administrations (to accelerate the growth of exporting industries), and modernization of government regulatory frameworks for the industry in various sectors (telecommunications, agriculture, and so forth). In USAID's early years and some larger programs, Economic Growth offices have financed economic infrastructure like roads and electrical power plants. Economic Growth assistance is thus quite diverse in terms of the range of sectors where it may work. It corresponds to USAID's socioeconomic development objective and is the source of sustainable poverty reduction. Economic Growth offices also occasionally manage assistance to poverty relief projects, such as to government programs that provide "cash transfer" payments to low-income families.

Special assistance

Some USAID missions have specialized technical offices for areas like counter-narcotics assistance or assistance in conflict zones.

Disaster assistance on a large scale is provided through USAID's Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance. Rather than having a permanent presence in country missions, this office has supplies pre-positioned in strategic locations to respond quickly to disasters when and where they occur.[48]

The Office of the Mission Director and the Program Office

The mission director's signature authorizes technical offices to assist according to the designs and budgets they propose. With the help of the Program Office, the mission director ensures that designs are consistent with USAID policy for the country, including budgetary earmarks by which Washington directs that funds be used for certain general purposes such as public health or environmental conservation. The Program Office compiles combined reports to Washington to support budget requests to Congress and to verify that budgets were used as planned.

Contracting, financial management and management offices

While the mission director is the public face and key decision-maker for an impressive array of USAID technical capabilities, arguably the offices that make USAID preeminent among U.S. government agencies in the ability to follow through on assistance agreements in low-income countries are the "support" offices.

Contracting

Commitments of U.S. government funds to NGOs and firms that implement USAID's assistance programs can only be made in compliance with carefully designed contracts and grant agreements executed by warranted Contracting and agreement officers. The mission director is authorized to commit financial assistance directly to the country's government agencies.

Financial management

Funds can be committed only when the Mission's Controller certifies their availability for the stated purpose. "FM" offices assist technical offices in financial analysis and in developing detailed budgets for inputs needed by projects assisted. They evaluate potential recipients' management abilities before financial assistance can be authorized and then review implementers' expenditure reports with great care. This office often has the largest number of staff of any office in the mission.

Management

Called the "Executive Office" in USAID (sometimes leading to confusion with the Embassy's Executive Office, which is the office of the Ambassador), "EXO" provides operational support for mission offices, including human resources, information systems management, transportation, property, and procurement services. Increasing integration into Embassies' chancery complexes, and the State Department's recently increased role in providing support services to USAID, is expanding the importance of coordination between USAID's EXO and the embassy's Management section.

Assistance projects

While the terms "assistance project" and "development project" might sometimes be used indiscriminately, it helps in understanding USAID's work to make a distinction. (1) Development is what developing countries do. Development projects are projects of local government agencies and NGOs, such as projects to improve public services or business regulations, etc. (2) Assistance is what USAID does. USAID's assistance projects support local development projects.

The key to a successful development project is the institutional capacity of local organizations, including the professional ability of their staff members. The key to successful assistance is how well it fits the needs of local development projects, including institutional capacity building and supporting professional education and training for staff.

When a local development project's assistance needs have been identified, USAID arranges the agreed assistance through funding agreements with implementing organizations, referred to by USAID staff as "implementing partners". USAID finances several types of implementers using a variety of funding agreements.

To illustrate, USAID might assist a development project with inputs provided through several different funding agreements:

- A budget-support grant to a government agency.

- A contract with a firm for support to the agency.

- A grant to a local NGO serving the beneficiary group.

- A grant to an international NGO to strengthen the operations of the local NGO.

Each of these types of USAID funding agreements is profiled below.

Budget support to a government agency

This funding agreement would take the form of a letter from USAID's mission director, countersigned by the recipient agency, explaining the agency's objectives, the amount of USAID's financial commitment, the specific expenditures to be financed by USAID's grant, and other operational aspects of the agreement.

USAID's technical office would assign a staff member (U.S. or local) to oversee progress in the agency's implementation. USAID's financial management office would transfer funds to the agency, in tranches as needed. Audit under this kind of government-to-government (G2G) financial assistance is usually performed by the host government's own audit agency.

Contract for technical assistance to a government agency

As a government agency is usually specialized in services to the beneficiary population (medical services, for example), its staff may not be equipped to undertake planning and evaluation, construction, acquisition of equipment, or management of training and study tours. The government agency might, therefore, request USAID's assistance in these areas, and USAID could respond by contracting with a firm to supply the services or technical assistance requested.

USAID's technical office would collaborate with the government agency in drafting the specifications for what is needed (generally referred to as a "Statement of Work" for the contract) and in conducting market research for available sources and potential bidders. USAID's contracting officer would then advertise for bids, manage the selection of a contractor from among the competing bidders, sign the contract, and assign a technical-office staff member as the contracting officer's representative to oversee the performance under the contract. (If the workload permits, this staff member might be the same person who oversees USAID's financial assistance to the government agency.)

The contractor supplies technical assistance directly to the government agency, so that in monitoring contractor performance USAID relies substantially on the agency's evaluation of the contractor's work.

Grant to finance NGO services to a beneficiary group

Non-governmental organizations are, like their government counterparts, usually already engaged in service provision in areas where USAID wants to assist, and they often have unique abilities that complement public programs. Therefore, USAID technical-office staff might set aside a budget and, with the help of the mission's contracting office, publish a solicitation for applications from NGOs for financial assistance to their programs. One or several grants could be made to selected NGOs by the contracting office's "agreement officer". Similar to the case of a contract, a USAID technical-office staff member would be assigned as the agreement officer's representative to monitor progress in the NGOs' implementation and to arrange for external evaluations. USAID grants require recipient NGOs to contract for external audits.

As some local NGOs may be small and young organizations with no prior experience in receiving awards from USAID, the USAID mission's financial management office reviews grant applicants' administrative systems to ensure that they are capable of managing U.S. government funds. Where necessary, USAID can devote part of the grant to the NGO's internal strengthening to help the NGO qualify for USAID's financing and build the capacity of the organization in the process. Following completion of the NGO's internal strengthening, USAID would disburse financing for the NGO's service project.

Grant to international NGOs for technical assistance

International NGOs have their own development projects and capabilities. If USAID and its counterparts determine that development objectives can best be met by supporting an NGO project, and if local NGO capacity is not yet sufficient, the relevant USAID technical office will draft a program description and the contracting office will issue as a request for applications to solicit responses from the international NGO community. USAID manages the award and implementation processes in the same way as for local NGOs.

Also, international NGOs frequently make unsolicited proposals to USAID, requesting funding for their own planned assistance activities. Where NGOs or business enterprises are dedicating a substantial amount of non-governmental resources to their projects, they can receive USAID funding through "Global Development Alliance" grants, provided that the non-governmental resources are at least equal in value to USAID's grant.

In general, USAID provides financial assistance to support other organizations' programs when those programs correspond to the areas that USAID wants to support, while USAID uses contracts to procure products or services requested by the leaders of local development projects.

Other mechanisms

In addition to the types of projects described above, USAID uses various other assistance mechanisms for different U.S. objectives.

Budget agreements

Budget agreements with other federal agencies are common in supporting collaboration between the U.S. and other countries on global issues. Large budget-support grants, referred to as "non-project" assistance, may be made to recipient governments to pursue U.S. foreign policy interests.

Cases of integration with U.S. military operations

In the exceptional circumstances of Vietnam in the 1960s and Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s, the government of the United States had USAID integrate selected staff with U.S. military units for "counterinsurgency" (COIN) operations.[49] The integrated institutions were "CORDS" in Vietnam ("Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support") and "PRTs" in Afghanistan and Iraq ("Provincial Reconstruction Teams").

Counterinsurgency operations were undertaken in localities where insurgents were vying with the national government for control. In Vietnam, for example, these were areas where there was what the United States government called "Viet Cong infrastructure".[50][51]

USAID's role was to assist the national government in strengthening its local governance and service capabilities, and in providing direct services to local residents.

In these areas, the national government could not provide physical security against attacks by insurgent forces. The role of the U.S. military assistance in COIN was, therefore, to combat insurgent military forces and to protect the civilian work of USAID and the national government. The military also contributed substantial resources for assistance projects.

The overall purpose of U.S. civilian-military assistance was to give the national government a capable and uncontested local presence.

In each of these countries, USAID also administered substantial conventional assistance programs that were not under the U.S. military chain of command.

The US military is assisting USAid in 2024.[52]

History

When the U.S. government created USAID in November 1961, it built on a legacy of previous development-assistance agencies and their people, budgets, and operating procedures. USAID's predecessor agency was already substantial, with 6,400 U.S. staff in developing-country field missions in 1961. Except for the peak years of the Vietnam War, 1965–70, that was more U.S. field staff than USAID would have in the future, and triple the number USAID has had in field missions in the years since 2000.[53]

After his inauguration as president on January 20, 1961, John F. Kennedy created the Peace Corps by Executive Order on March 1, 1961. On March 22, he sent a special message to Congress on foreign aid, asserting that the 1960s should be a "Decade of Development" and proposing to unify U.S. development assistance administration into a single agency. He sent a proposed "Act for International Development" to Congress in May and the resulting "Foreign Assistance Act" was approved in September, repealing the Mutual Security Act. In November, Kennedy signed the act and issued an Executive Order tasking the Secretary of State to create, within the State Department, the "Agency for International Development" (or A.I.D.: subsequently re-branded as USAID),[a] as the successor to both ICA and the Development Loan Fund.[b] With these actions, the U.S. created a permanent agency working with administrative autonomy under the policy guidance of the State Department to implement, through resident field missions, a global program of both technical and financial development assistance for low-income countries. This structure has continued to date.[c]

Second Trump administration

In January 2025, President Donald Trump ordered a near-total freeze on all foreign aid.[6][7] Several days later, Secretary of State Marco Rubio issued a waiver for humanitarian aid.[54][55] Despite the waiver, there was still much confusion about what agencies should do.[56] More than 1,000 USAID employees and contractors were fired or furloughed following the near-total freeze on U.S. global assistance that the second Trump administration implemented.[57] Matt Hopson, the USAID chief of staff appointed by the Trump administration, has resigned.[58][59]

On January 27, 2025, the agency's official government website was shut down.[60] On February 3, 2025, Elon Musk, director of the Department of Government Efficiency, announced that he and Trump were in the process of shutting down USAID, claiming it to be a "criminal organization" and that it was "beyond repair".[8][61] Also on February 3, Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced that he had been appointed Acting Administrator of USAID by Trump and that the agency was being merged into the State Department.[62] The legality of these actions is disputed given the mandate for its creation in the Foreign Assistance Act.[63][64][65]

Budget

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Out of date and website referred to currently shut down. (February 2025) |

| Nation | Billions of Dollars |

|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 2.24 |

| Pakistan | 0.97 |

| Jordan | 0.48 |

| Ethiopia | 0.45 |

| Haiti | 0.31 |

| Kenya | 0.31 |

| Iraq | 0.28 |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 0.24 |

| Uganda | 0.22 |

| Tanzania | 0.21 |

| Somalia | 0.20 |

| West Bank and Gaza | 0.20 |

| Ghana | 0.19 |

| Bangladesh | 0.18 |

| Colombia | 0.18 |

| Indonesia | 0.17 |

| Liberia | 0.16 |

| Yemen | 0.16 |

| Mozambique | 0.16 |

| India | 0.15 |

The cost of supplying USAID's assistance includes the agency's "Operating Expenses", $1.53 billion in fiscal year 2012, and "Bilateral Economic Assistance" program costs, $20.83 billion in fiscal year 2012 (the vast bulk of which was administered by USAID).[66] In fiscal year 2022, "Operating Expenses" were $1.97 billion, and "Bilateral Economic Assistance" was $25.01 billion.[67]

Up-to-date details of the budget for USAID's assistance and other aspects of U.S. foreign assistance are available from USAID's budget webpage.[68] This page contains a link to the Congressional Budget Justification, which shows the U.S. Government's Foreign Operations budget (the "150 Account") for all International Affairs programs and operations for civilian agencies, including USAID. This page also has a link to a "Where Does the Money Go?" table, which shows the recipients of USAID's financial assistance (foreign governments as well as NGOs), the totals that were spent for various countries, and the sources (U.S. government agencies, universities, and private companies) from which USAID procured the goods and services that it provided as technical assistance.

U.S. assistance budget totals are shown along with other countries' total assistance budgets in tables in a webpage of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.[69]

At the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, most of the world's governments adopted a program for action under the auspices of the United Nations Agenda 21, which included an Official Development Assistance (ODA) aid target of 0.7% of gross national product (GNP) for rich nations, specified as roughly 22 members of the OECD and known as the Development Assistance Committee (DAC). Most countries do not adhere to this target, as the OECD's table indicates that the DAC average ODA in 2011 was 0.31% of GNP. The U.S. figure for 2011 was 0.20% of GNP, which still left the U.S. as the largest single source of ODA among individual countries. According to the OECD, The United States' total official development assistance (ODA) (US$55.3 billion, preliminary data) increased in 2022, mainly due to support to Ukraine, as well as increased costs for in-donor refugees from Afghanistan. ODA represented 0.22% of gross national income (GNI).[70]

Activities by region

Haiti

Following the January 2010 earthquake in Haiti, USAID helped provide safer housing for almost 200,000 displaced Haitians; supported vaccinations for more than 1 million people; cleared more than 1.3 million cubic meters of the approximately 10 million cubic meters of rubble generated; helped more than 10,000 farmers double the yields of staples like corn, beans, and sorghum; and provided short-term employment to more than 350,000 Haitians, injecting more than $19 million into the local economy. USAID has provided nearly $42 million to help combat cholera, helping to decrease the number of cases requiring hospitalization and reduce the case fatality rate.[citation needed]

Afghanistan

With American entry into Afghanistan in 2001, USAID worked with the Department of State and Department of Defense to coordinate reconstruction efforts.[71]

Iraq

The interactions between USAID and other U.S. government agencies in the period of planning the Iraq operation of 2003 are described by the Office of the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction in its book Hard Lessons: The Iraq Reconstruction Experience.[72]

Subsequently, USAID played a major role in the U.S. reconstruction and development effort in Iraq. As of June 2009[update], USAID had invested approximately $6.6 billion on programs designed to stabilize communities; foster economic and agricultural growth; and build the capacity of the national, local, and provincial governments to represent and respond to the needs of the Iraqi people.[73]

In June 2003, C-SPAN followed USAID administrator Andrew Natsios as he toured Iraq. The special program C-SPAN produced aired over four nights.[74]

Lebanon

USAID has periodically supported the Lebanese American University and the American University of Beirut financially, with major contributions to the Lebanese American University's Campaign for Excellence.[75]

Cuba

A USAID subcontractor was arrested in Cuba in 2009 for distributing satellite equipment to provide Cubans with internet access. The subcontractor was released during Obama's second presidential term as part of the measures to improve relations between the two countries.[76]

USAID has been used as a mechanism for "hastening transition", i.e. regime change in Cuba.[77] Between 2009 and 2012, USAID ran a multimillion-dollar program, disguised as humanitarian aid and aimed at inciting rebellion in Cuba. The program consisted of two operations: one to establish an anti-regime social network called ZunZuneo, and the other to attract potential dissidents contacted by undercover operatives posing as tourists and aid workers.[78][79]

USAID engineered a subversive program using social media aimed at fueling political unrest in Cuba to overthrow the Cuban government. On 3 April 2014 the Associated Press published an investigative report that revealed USAID was behind the creation of a social networking text messaging service aimed at creating political dissent and triggering an uprising against the Cuban government.[80] The name of the messaging network was ZunZuneo, a Cuban slang term for a hummingbird's tweet and a play on "Twitter". According to the AP's report, the plan was to build an audience by initially presenting non-controversial content like sports, music and weather. Once a critical mass of users was reached the US government operators would change the content to spark political dissent and mobilize the users into organized political gatherings called "smart mobs" that would trigger an uprising against the Cuban government.[80]

The messaging service was launched in 2010 and gained 40,000 followers at its peak. Extensive efforts were made to conceal the USAID involvement in the program, using offshore bank accounts, front companies and servers based overseas.[81] According to a memo from one of the project's contractors, Mobile Accord: "There will be absolutely no mention of United States government involvement," "This is absolutely crucial for the long-term success of the service and to ensure the success of the Mission."[80] ZunZuneo's subscribers were never aware that it was created by the US government or that USAID was gathering their private data to gain useful demographics that would gauge their levels of dissent and help USAID "maximize our possibilities to extend our reach".[80]

USAID officials realized they needed an exit strategy to conceal their involvement in the program, at one point seeking funding from Twitter cofounder Jack Dorsey as part of a plan for it to go independent.[80] The service was abruptly closed down around mid-2012, which USAID said was due to the program running out of money.[82]

The ZunZuneo operation was part of a program that included a second operation which started in October 2009 and was financed jointly with ZunZuneo. In the second operation, USAID sent Venezuelan, Costa Rican and Peruvian children to Cuba to recruit Cubans into anti-regime political activities. The operatives posed as traveling aid workers and tourists. In one of the covert operations, the workers formed a HIV prevention workshop, which leaked memos called "the perfect excuse" for the programme's political goals. The Guardian said the operation could undermine US efforts to work toward improving health globally.[78]

The operation was also criticized for putting the undercover operatives themselves at risk. The covert operatives were given limited training about evading Cuban authorities suspicious of their actions. After Alan Gross, a development specialist and USAID subcontractor, was arrested in Cuba, the US government warned USAID about the safety of covert operatives. Regardless of safety concerns, USAID refused to end the operation.[78]

In light of the AP's report, Rajiv Shah, the head of USAID, was scheduled to testify before the Senate Appropriations State Department and Foreign Operations Subcommittee on 8 April 2014.[83]

Bolivia

USAID operated in the coca-growing Chapare region, including under a 1983 agreement to support crop-substitution programs to encourage other crops.[84] No later than 1998, this funding was conditional on farmers eradicating all their coca plants.[85] In 2008, the coca growers union affiliated with Bolivian President Evo Morales ejected the 100 employees and contractors from USAID working in the Chapare region, citing frustration with U.S. efforts to persuade them to switch to growing unviable alternatives.[86] Other rules, such as the requirement that participating communities declare themselves "terrorist-free zones" as required by U.S. law irritated people, said Kathryn Ledebur, director of the Andean Information Network. "Eradicate all your coca and then you grow an orange tree that will get fruit in eight years but you don't have anything to eat in the meantime? A bad idea. The thing about kicking out USAID, I don't think it's an anti-American sentiment overall but rather a rejection of bad programs."[85]

Also in 2008, USAID's Bolivian programs under the Office of Transitional Initiatives and the Democracy Program, as well as separate funding by the National Endowment for Democracy, were the subject of critical investigative reports[87][88] that documented them supporting political initiatives in regions governed by separatist movements. During the September 2008 political crisis, President Evo Morales expelled US Ambassador Philip S. Goldberg and spoke out against USAID interference.[89] The US government had previously ended OTI spending in Bolivia and subsequently redirected Democracy Program funds to other purposes, while denying USAID had interfered in Bolivian politics.[89][90]

President Evo Morales expelled USAID from Bolivia on May 1, 2013, for allegedly seeking to undermine his government following ten years of operations within the country.[91] At the time, the USAID had seven American staffers and 37 Bolivian staffers in the country, with an annual budget of $26.7 million.[92] President Morales explained that the expulsion was because USAID's objectives in Bolivia were to advance American interests, not to advance the interests of the Bolivian people. More specifically, President Morales noted the American "counter-narcotic" programs that harms the interests of Bolivian coca farmers who get caught in the middle of American operations.[91]

Following the 2019 Bolivian political crisis that saw Jeanine Áñez's assumption of power, President Áñez invited USAID to return to Bolivia to provide "technical aid to the electoral process in Bolivia".[93] In October 2020, USAID provided $700,000 in emergency assistance in fighting wildfires to the goverment of Luis Arce.[94]

East Africa

On September 19, 2011, USAID and the Ad Council launched the "Famine, War, and Drought" (FWD) campaign to raise awareness about that year's severe drought in East Africa. Through TV and internet ads as well as social media initiatives, FWD encouraged Americans to spread awareness about the crisis, support the humanitarian organizations that were conducting relief operations, and consult the Feed the Future global initiative for broader solutions. Celebrities Geena Davis, Uma Thurman, Josh Hartnett and Chanel Iman took part in the campaign via a series of Public Service Announcements. Corporations like Cargill, General Mills, PepsiCo. and General Mills also signed on to support FWD.[95]

Palestinian territories

USAID ended all its projects in the West Bank and Gaza Strip on January 31, 2019.[96] On November 10, 2023, more than 1,000 employees of USAID signed an open letter calling for an immediate ceasefire in the Israel–Hamas war.[97]

Vietnam

USAID, alongside the Department of State and Defence, has supported NGOs to removing UXO and landmines, and remediating soil contaminated by Agent Orange from multiple regions in Vietnam,[98][99][100] as well as supporting victims of Agent Orange.[101][102]

Controversies and criticism

USAID and U.S. foreign economic assistance in general have been the subject of debate, controversy, and criticism continuously since the 1950s.

Non-career contracts

USAID frequently contracts with private firms or individuals for specialist services lasting from a few weeks to several years. It has long been asked whether USAID should more often assign such tasks to career U.S. government employees instead. United States government staff directly performed technical assistance in the earliest days of the program in the 1940s. It soon became necessary for the federal government technical experts to plan and manage larger assistance programs than they could perform by themselves. The global expansion of technical assistance in the early 1950s reinforced the need to draw on outside experts, which was also accelerated by Congress's requirement of major reductions of U.S. government staffing in 1953. By 1955, observers commented on a perceived shift toward re use of shorter-term contracts (rather than using employees with career-length contracts).[103][104]

Financial conflicts of interest

USAID states that "U.S. foreign assistance has always had the twofold purpose of furthering America's foreign policy interests in expanding democracy and free markets while improving the lives of the citizens of the developing world." Non-government organization watch groups have noted that as much as 40% of aid to Afghanistan has found its way back to donor countries through awarding contracts at inflated costs.[105]

Although USAID officially selects contractors on a competitive and objective basis, watchdog groups, politicians, foreign governments, and corporations have occasionally accused the agency of allowing its bidding process to be unduly influenced by the political and financial interests of its current presidential administration. Under the Bush administration, for instance, it emerged that all five implementing partners selected to bid on a $600 million Iraq reconstruction contract enjoyed close ties to the administration.[106][107]

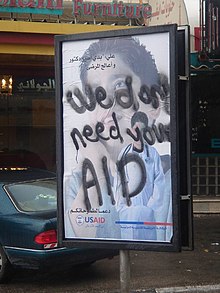

Political operations abroad

William Blum has said that in the 1960s and early 1970s USAID has maintained "a close working relationship with the CIA, and Agency officers often operated abroad under USAID cover."[108] The 1960s-era Office of Public Safety, a now-disbanded division of USAID, has been mentioned as an example of this, having served as a front for training foreign police in counterinsurgency methods (including torture techniques).[109]

Folha de S.Paulo, Brazil's largest newspaper, accused USAID of trying to influence political reform in Brazil in a way that would have purposely benefited right-wing parties. USAID spent $95,000 US in 2005 on a seminar in the Brazilian Congress to promote a reform aimed at pushing for legislation punishing party infidelity. According to USAID papers acquired by Folha under the Freedom of Information Act, the seminar was planned to coincide with the eve of talks in that country's Congress on a broad political reform. The papers read that although the "pattern of weak party discipline is found across the political spectrum, it is somewhat less true of parties on the liberal left, such as the [ruling] Worker's Party." The papers also expressed a concern about the "'indigenization' of the conference so that it is not viewed as providing a U.S. perspective." The event's main sponsor was the International Republican Institute.[110]

In 2008, Benjamin Dangl wrote in The Progressive that the Bush administration was using USAID to fund efforts in Bolivia to "undermine the Morales government and coopt the country’s dynamic social movements – just as it has tried to do recently in Venezuela and traditionally throughout Latin America".[111]

From 2010 to 2012, the agency operated ZunZuneo,[112] a social media site similar to Twitter in an attempt to instigate uprisings against the Cuban government. Its involvement was concealed in order to ensure mission success. The plan was to draw in users with non-controversial content until a critical mass is reached, after which more political messaging would be introduced. At its peak, more than 40,000 unsuspecting Cubans interacted on the platform.[112]

In the summer of 2012, ALBA countries (Venezuela, Cuba, Ecuador, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Dominica, Antigua and Barbuda) called on its members to expel USAID from their countries.[113]

Influence on the United Nations

Several studies[which?] suggest that foreign aid is used as a political weapon for the U.S. to elicit desired actions from other nations. A state's membership of the U.N. Security Council can give a considerable raise of U.S. assistance.[114]

In 1990 when the Yemeni Ambassador to the United Nations, Abdullah Saleh al-Ashtal, voted against a resolution for a U.S.-led coalition to use force against Iraq, U.S. ambassador to the UN Thomas Pickering walked to the seat of the Yemeni Ambassador and retorted: "That was the most expensive No vote you ever cast". Immediately, USAID ceased operations and funding in Yemen.[115][116]

State Department terrorist list

USAID requires NGOs to sign a document renouncing terrorism, as a condition of funding. Issam Abdul Rahman, media coordinator for the Palestinian Non-Governmental Organizations' Network, a body representing 135 NGOs in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, said his organization "takes issue with politically conditioned funding". Also, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, listed as a terrorist organization by the US Department of State, said that the USAID condition was nothing more than an attempt "to impose political solutions prepared in the kitchens of Western intelligence agencies to weaken the rights and principles of Palestinians, especially the right of return."[117]

Renouncing prostitution and sex trafficking

In 2003, Congress passed a law providing U.S. government funds to private groups to help fight AIDS and other diseases all over the world through USAID grants. One of the conditions imposed by the law on grant recipients was a requirement to have "a policy explicitly opposing prostitution and sex trafficking".[118] In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Agency for International Development v. Alliance for Open Society International, Inc. that the requirement violated the First Amendment's prohibition against compelled speech.[119]

Involvement in Peru's forced sterilizations

During the 1990s, USAID was implicated in the forced sterilization of approximately 300,000 indigenous women in Peru as part of the country's Plan Verde. Population control guidelines promoted by international bodies, including USAID, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the Nippon Foundation, supported the Fujimori government's sterilization efforts.[120][121] Investigations by Peru's congressional subcommittee found a causal correlation between increased USAID funding and the number of sterilizations performed.[121] These sterilizations were part of a global strategy by the United States government to reduce birth rates in developing countries for political and economic stability.[121]

Documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act revealed that USAID effectively took control of Peru's national health system from 1993 to 1998, during the period of forced sterilizations. It was concluded that it would be virtually inconceivable for these sterilization abuses to have occurred systematically without the knowledge of USAID administrators in Peru and Washington.[120][121]

Under pressure from investigations by the Population Research Institute, USAID ceased funding for sterilizations in Peru in 1998. The forced sterilizations continued until President Fujimori fled to Japan in 2000.[122] The policy resulted in a generational shift, creating a smaller younger generation unable to provide economic stimulation to rural areas, thus increasing poverty in those regions.[122]

Office of Inspector General investigation into alleged terror-linked funding

According to a February 2024 report, the USAID's Office of Inspector General launched an investigation in 2023 into the agency for awarding $110,000 in 2021 to Helping Hand for Relief and Development (HHRD), a charity in Michigan that Republicans on the House Foreign Affairs Committee have accused in recent years of sharing ties to terrorism organizations in South Asia.[123][124][125] In August 2023, USAID's Vetting Support Unit cleared HHRD to receive the grant.[126] In 2024, researchers at George Mason University reported that allegations against HHRD were part of a campaign targeting large American Muslim charities based on the manipulation of poorly-sourced information.[127]

See also

- African Development Foundation

- Chemonics International

- Development Alternatives Inc.

- Development Experience Clearinghouse

- Feed the Future Initiative

- Food for Peace

- Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition

- Hard Choices

- John Granville

- List of development aid agencies

- Office of Transition Initiatives

- POPLINE

- Strengthening Emergency Response Abilities (SERA) Project

- The INFO Project

- U.S. International Development Finance Corporation

- United States foreign aid

- United States military aid

Notes

- ^ The names of predecessor agencies often continued in popular usage. In Vietnam in the 1960s, it was common to refer to A.I.D.'s office as "USOM," while in Peru A.I.D. telephone operators continued in the 1960s to answer calls saying "Punto Cuatro" (Point Four).[citation needed]

- ^ In 1966, the UN would also integrate its EPTA and the Special Fund into a new agency, the UN Development Program, or UNDP.[citation needed]

- ^ The Fulbright educational and cultural exchange program was also strengthened by the Fulbright-Hays Act in September 1961.[citation needed]

References

- ^ "Agency Financial Report, FY 2016" (PDF). USAID. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 5, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ "USAID History". USAID. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ "Marco Rubio appoints himself head of USAid as workers locked out of office". The Guardian. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ "Agency for International Development". USASpending.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Bork, Timothy (November–December 2011). "Mission to South Africa". Frontlines.

U.S. policy was to help bring an end to apartheid and establish a nonracial, democratic government. In response to this policy and the Act, USAID/South Africa was responsible for financing projects that apartheid victims viewed as critical in promoting social, political, and economic change through peaceful means.

- ^ a b Thomas Escritt; Poppy McPherson; Jennifer Rigby (January 29, 2025). "Trump's freeze on US aid rings alarm bells from Thailand to Ukraine". MSN. Retrieved January 29, 2025.

- ^ a b Knickmeyer, Ellen; Amiri, Farnoush (January 24, 2025). "State Department freezes new funding for nearly all US aid programs worldwide". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 29, 2025.

- ^ a b Hansler, Jennifer; Marquardt, Alex; Harvey, Lex (February 2, 2025). "Elon Musk said Donald Trump agreed USAID needs to be 'shut down'". CNN Politics. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ "USAID History". usaid.gov. USAID. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ^ "USAID: Automated Directives System 400" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 19, 2003. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ USAID. "ADS Chapter 101.2 Agency Programs and Functions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 18, 2003. Retrieved December 22, 2011.

- ^ "USAID Primer: What We Do and How We Do It" (PDF). Development Experience Clearinghouse. USAID. January 2006. Retrieved July 16, 2018. Each particular official statement of USAID's goals is specific to the U.S. foreign-policy emphases of the moment the statement is made. The best official statement relevant to the most recent era is in USAID's 2004 "White Paper," reaffirmed in high-level USAID policy documents in 2006 and 2011. (See the references USAID authored at the end of this article.) To give a perspective of USAID's goals that are as general as possible, the list of goals in this article subsumes one of the goals from the 2004 White Paper, "Strengthen fragile states," whose emphasis as understood at the time was on Iraq and Afghanistan, into a more general goal, "U.S. national interests," together with one of the White Paper's other goals, "Support strategic states." State fragility is understood to be one of the development issues addressed under this article's "Socioeconomic development" goal. On the other hand, the White Paper's goal, "Provide humanitarian relief," is divided in this article into two goals, both of which are humanitarian: "Disaster relief" (which may assist victims at various income levels) and "Poverty relief" (which targets chronic poverty, not just the result of a disaster, and which does not necessarily have to be justified by a developmental impact).

- ^ "Global Climate Change: Capacity Building". USAID. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ Tarnoff (2015), p. 13.

- ^ Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (as amended), Section 531.

- ^ "Stabilization: Lessons from the U.S. Experience in Afghanistan". SIGAR. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "ADS Chapter 310: Source and Nationality Requirements for Procurement of Commodities and Services Financed by USAID" (PDF). USAID. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "USAID Primer: What We Do and How We Do It". Usaid.gov. December 8, 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ "USAID Signs Partnership with the Global Food Safety Initiative". usaid.gov. United States Agency for International Development. April 26, 2023.

- ^ "USAID: Organization". Usaid.gov. March 4, 2011. Archived from the original on April 23, 2011. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ USAID (2003). "ADS Chapter 349" (PDF). p. Section 349.3.1.1. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ USAID (2004). "ADS Chapter 155" (PDF). p. Section 155.3.1.1.c. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ Tarnoff, Curt (July 21, 2015). "U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID): Background, Operations, and Issues" (PDF). Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ "South Korea: From Aid Recipient to Donor" (PDF). USAID. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "Mission Directory". USAID. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ Mohammed, Arshad (September 18, 2012). "USAID mission in Russia to close following Moscow decision". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ "Bolivia's President Morales expels USAID, accused it of working against him". Washington Post. May 1, 2013. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013.

- ^ "ADS Chapter 436: Foreign Service Assignments and Tours of Duty" (PDF). USAID. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 4, 2017. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ Dorman, Shawn. "Foreign Service Work and Life: Embassy, Employee, Family" (PDF). American Foreign Service Association. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "Organization". USAID. February 16, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ^ "Global Health Programs: Report to Congress FY 2014". usaid.gov. July 12, 2021.

- ^ "Maternal and Child Health". usaid.gov. June 4, 2019. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ^ Call to Action on Child Survival

- ^ "Maternal, newborn and child survival". www.unicef.org.

- ^ "USAID DRG Bureau". USAID Democracy. Retrieved October 3, 2023.

- ^ "DRGLinks". DRGLinks. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Global Development Lab". Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ "USAID Staffing Report to Congress" (PDF). USAID. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 3, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ USAID (2014). "ADS Chapter 495: Foreign Service National Personnel Administration" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ See ADS section 495.3.1.

- ^ ADS section 495.3.4; Koehring et al. (1992), pp. 17, 28.

- ^ "USAID Foreign Service". USAID. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ "Foreign Service Test Information". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ "Survey of USAID's Development Leadership Initiative in Southern and Eastern Africa" (PDF). USAID Inspector General. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ "Mission". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on December 15, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ "ADS Chapter 102: Agency Organization" (PDF). USAID. 2012. p. 23. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017. See in particular the definitions of "Large mission" and "Office."

- ^ Shen, Jianzhong; Schwarz, Stefan (March 29, 2023). "Introducing One Health Advances: a new journal connecting the dots for global health". One Health Advances. 1 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/s44280-023-00011-1. ISSN 2731-9970. PMC 10049891. PMID 37521534.

- ^ "Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance". USAID. November 15, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ Coffey, Ross (Major, U.S. Army) (March–April 2006). "Revisiting CORDS: The Need for Unity of Effort to Secure Victory in Iraq". Military Review: 24–34. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Coffey. p. 31

- ^ Jones, Robert Leith (2013). Blowtorch: Robert Komer, Vietnam, and American Cold War Strategy. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781612512280.

- ^ Youssef, Nancy A. (May 28, 2024). "Pentagon Shuts Down Floating Pier for Gaza Aid After Storm Damage". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 5, 2024.

- ^ Data from USAID reports, "Distribution of Personnel as of June 30, 1949 thru 1976," "Supporting the USAID Mission, and the "USAID Staffing Report to Congress" of 2016. See full citations in "References," below.

- ^ "Rubio backtracks on near total foreign aid freeze, issues humanitarian waiver". Washington Post. January 28, 2025. Retrieved January 29, 2025.

- ^ Hansler, Jennifer (January 29, 2025). "As humanitarian officials warn people could die as a result of Trump's foreign aid halt, Rubio issues new waiver". CNN Politics. Retrieved January 29, 2025.

- ^ Rigby, Jennifer; Kumwenda-Mtambo, Olivia; Fick, Maggie (January 29, 2025). "Despite waiver from U.S. on aid freeze, health and humanitarian groups uncertain if they can proceed". Reuters. Retrieved January 29, 2025.

- ^ Williams, Abigail; Hillyard, Vaughn; Alcindor, Yamiche (February 2, 2025). "USAID security leaders removed after refusing Elon Musk's DOGE employees access to secure systems". NBC News.

- ^ Landay, Jonathan; Zengerle, Patricia; Shalal, Andrea (February 3, 2025). "More USAID staff ousted after Trump administration dismantles aid agency". Reuters. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ Steakin, Will; Travers, Karen; Siegel, Benjamin; Parks, MaryAlice; Kingston, Shannon K.; Faulders, Katherine (February 3, 2025). "Turmoil inside USAID: DOGE reps take over offices, senior officials placed on leave". ABC News. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ Schreiber, Melody (February 3, 2025). "Why does Musk want USAID 'to die'? And why did its website disappear?". NPR. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ "Elon Musk says he and Trump are shutting down USAID". NBC News. February 3, 2025. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ Cook, Sara; Jacobs, Jennifer (February 3, 2025). "USAID to be merged into State Department, 3 U.S. officials say". CBS News.

- ^ "Trump administration explores brining USAID under state department". Reuters. January 31, 2025.

- ^ Novak, Matt (February 1, 2025). "USAID Website Goes Offline as Trump Continues to Dismantle Government". Gizmodo.

- ^ Murray, Conor (February 1, 2025). "USAID Website Appears To Be Offline As Trump Administration Reportedly Moves To Put It Under State Department Control". Forbes.

- ^ "FUNCTION 150 & OTHER INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. April 10, 2013. pp. 63, 66. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 30, 2013.

- ^ "FY 2024 Congressional Budget Justification - Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. March 13, 2023. p. 95. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 5, 2024.

- ^ "Budget – U.S. Agency for International Development". usaid.gov. March 11, 2019.

- ^ "Aid statistics". OECD. December 23, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ^ "OECD Development Co-operation Profiles". Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ Spoko, John (2013). "Afghanistan Reconstruction: Lessons from the Long War". PRISM. 8 (2): 26–39. JSTOR 26803228.

- ^ "Hard Lessons: The Iraq Reconstruction Experience" (PDF). US Special Inspector General – Iraq Reconstruction. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2013. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ "Assistance for Iraq". USAID. Archived from the original on November 14, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ "Rebuilding Iraq". C-SPAN. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ "The Legacy and the promise (Lebanese American University)". Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ Augustin, Ed; Montero, Daniel (August 3, 2021). "Why the internet in Cuba has become a US political hot potato". the Guardian. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ "USAID DAI Contract - United States Agency For International Development – Cuba". Scribd.

- ^ a b c "USAID programme used young Latin Americans to incite Cuba rebellion". The Guardian. August 4, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ^ "US secretly created 'Cuban Twitter' to stir unrest and undermine government". The Guardian. Associated Press. April 3, 2014. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "US secretly created 'Cuban Twitter' to stir unrest". Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Lewis, Paul; Roberts, Dan (April 3, 2014). "White House denies 'Cuban Twitter' ZunZuneo programme was covert". The Guardian. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ Toor, Amar (April 3, 2014). "US government harassed Castro with a fake Twitter service". The Verge. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ "US agency that created 'Cuban Twitter' faces political firestorm". Ars Technica. April 4, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ Rasnake, Roger Neil; Painter, Michael (1989). Rural development and crop substitution in Bolivia: USAID and the Chapare regional development project. Working Paper - Institute for Development Anthropology.

- ^ a b Partlow, Joshua (September 4, 2008). "Ecuador Giving U.S. Air Base the Boot". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ Andean Information Network, 27 June 2008, "Bolivian coca growers cut ties with USAID"

- ^ Dangl, Benjamin (February 1, 2008). "Undermining Bolivia". Progressive.org. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ "USAID's Silent Invasion in Bolivia". NACLA. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ a b Romero, Simon (September 27, 2008). "Fears of Turmoil Persist as Powerful President Reshapes Bitterly Divided Bolivia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ Wolff, Jonas (2017). "Negotiating interference: US democracy promotion, Bolivia and the tale of a failed agreement". Third World Quarterly. 38 (4): 882–899. ISSN 0143-6597. JSTOR 26156150. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ a b "Bolivian President Evo Morales expels USAID". BBC News. May 1, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ "Bolivia and USAID (Taken Question)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ "Interim Bolivian president Añez calls Indigenous citizens 'savages'". People's World. January 28, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ U.S. Agency for International Development (October 14, 2020). "Bolivia | Humanitarian Assistance | Archive". 2017-2020.usaid.gov. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ "New PSAs: 'FWD' Awareness About the Horn of Africa Crisis". Ad Age. October 26, 2011

- ^ "'USAID to end all Palestinian projects on Jan. 31,' former director says – Arab-Israeli Conflict – Jerusalem Post". jpost.com. January 17, 2019.

- ^ Pamuk, Humeyra; Lewis, Simon (November 10, 2023). "Over 1,000 USAID officials call for Gaza ceasefire in letter". Reuters.

- ^ "Fact Sheets: UNEXPLODED ORDNANCE (UXO) REMOVAL". U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Vietnam. July 28, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2025.

- ^ Mai, Lauren; Poling, Gregory B.; Quitzon, Japhet (August 19, 2024). "An Indispensable Upgrade: The U.S.-Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership". CSIS.org. Retrieved February 4, 2025.

- ^ "US adds $130M to dioxin cleanup project at Vietnam airport, one of world's most contaminated regions". VNexpress. January 18, 2025. Retrieved February 4, 2025.

- ^ "USAID-funded project improves livelihood for AO victims". VietnamPlus. August 15, 2023. Retrieved February 4, 2025.

- ^ "U.S. Agent Orange/Dioxin Assistance to Vietnam" (PDF). sgp.fas.org. January 15, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2025.

- ^ Richardson. Partners in Development. pp. 13–14, 37.

- ^ Butterfield (2004), pp. 25–26.

- ^ Richard Norton-Taylor 40% of Afghan aid returns to donor countries, says report guardian.co.uk 25 March 2008

- ^ Barbara Slavin Another Iraq deal rewards company with connections USA Today 4/17/2003

- ^ Tran, Mark (March 31, 2003). "Halliburton misses $600m Iraq contract". The Guardian.

- ^ William Blum, Killing hope : U.S. military and CIA interventions since World War II Zed Books, 2003, ISBN 978-1-84277-369-7 pp. 142, 200, 234.

- ^ Michael Otterman, American torture: from the Cold War to Abu Ghraib and beyond (Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press, 2007), p. 60.

- ^ "EUA tentaram influenciar reforma política do Brasil". .folha.uol.com.br. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ Dangl, Benjamin (February 1, 2008). "Undermining Bolivia". Progressive.org. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ a b "US secretly created 'Cuban Twitter' to stir unrest and undermine government". The Guardian. Associated Press. April 3, 2014. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "After More Than 50 Years, USAID Is Leaving Ecuador". NBC News. October 1, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Security Council Seat Tied to Aid". Globalpolicy.org. November 1, 2006. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ Hornberger, Jacob" But Foreign Aid Is Bribery! And Blackmail, Extortion, and Theft Too!" September 26, 2003

- ^ U.S. State Department, Country Fact Sheets – Background Note: Yemen. 12 March 2012

- ^ Sterman, Adiv (January 31, 2013). "How dare you make us cooperate with Israel, Palestinian NGOs protest to EU". Timesofisrael.com. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (June 20, 2013). "Justices Say U.S. Cannot Impose Antiprostitution Condition on AIDS Grants". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- ^ Roberts, John (June 20, 2013). "Agency for International Development v. Alliance for Open Society International, Inc". Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law School. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ^ a b McMaken, Ryan (October 26, 2018). "How the U.S. Government Led a Program That Forcibly Sterilized Thousands of Poor Peruvian Women in the 1990s". Foundation for Economic Education. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Informe final sobre la aplicación de la anticoncepción quirúrgica voluntaria (AQV) en los años 1990–2000" (PDF). Congress of Peru. June 2002.

- ^ a b "Mass sterilisation scandal shocks Peru". BBC News. July 24, 2002. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ Kaminsky, Gabe (February 28, 2024). "USAID watchdog began investigating tax dollars to a terrorism-tied NGO. Then Biden sent it more cash – Washington Examiner". Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ "McCaul Demands Answers From USAID on Alarming Failure to Address $110K Grant to Terrorist-Linked Nonprofit". Committee on Foreign Affairs. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ Walker, Jackson (February 28, 2024). "Biden admin sent cash to non-profit under investigation for terrorism links, report says". The National Desk. Retrieved March 10, 2024.