East Jerusalem

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

|

East Jerusalem (Arabic: القدس الشرقية, al-Quds ash-Sharqiya; Hebrew: מִזְרַח יְרוּשָׁלַיִם, Mizraḥ Yerushalayim) is the portion of Jerusalem that was held by Jordan after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, as opposed to West Jerusalem, which was held by Israel.[a] Under international law, East Jerusalem is considered part of the West Bank, and Palestinian territories, and under illegal occupation by Israel.[2][3][4] Many states recognize East Jerusalem as the capital of the State of Palestine (such as Brazil,[5] China,[6] Russia,[7] and all 57 members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation),[8] whereas other states (such as Australia, France and others) assert that East Jerusalem "will be the capital of Palestine",[9][10] while referring to it as "an occupied territory".[11] In 2020, East Jerusalem had a population of 595,000 inhabitants, of which 361,700 (61%) were Palestinian Arabs and 234,000 (39%) Jewish settlers.[12][13] Israeli settlements in East Jerusalem are illegal under international law and in the eyes of the international community.[14][15]

Jerusalem was envisaged as a separate, international city under the 1947 UN partition plan. It was, however, divided by the 1948 war that followed Israel's declaration of independence. As a result of the 1949 Armistice Agreements, the city's western half came under Israeli control, while its eastern half, containing the famed Old City, fell under Jordanian control.[16][b] Israel occupied East Jerusalem during the 1967 Six-Day War; since then, the entire city has been under Israeli control. The 1980 Jerusalem Law declared unified Jerusalem the capital of Israel,[18] formalizing the effective annexation of East Jerusalem. Palestinians and many in the international community consider East Jerusalem to be the future capital of the State of Palestine. The status of Jerusalem has been described as "one of the most intractable issues in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict", with conflicting claims to sovereignty over the city or parts of it, and access to its holy sites.[19]

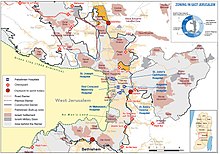

Israeli and Palestinian definitions of East Jerusalem differ.[c] Following the 1967 Six-Day War, Jerusalem's municipal boundaries were extended totaling an area three times the size of pre-war West Jerusalem. This includes several West Bank villages to the north, east and south of the Old City that are now considered neighborhoods of the city, as well as eight suburban neighborhoods that were built since then. The international community considers these neighborhoods illegal settlements, but the Israeli government disputes this. The Israeli position is based on the extended municipal boundaries, while the Palestinian position is based on the 1949 Agreements.

East Jerusalem includes the Old City, which is home to many sites of seminal religious importance for the three major Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, including the Temple Mount / Al-Aqsa, the Western Wall, the Dome of the Rock and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Arab residents of East Jerusalem are increasingly becoming integrated into Israeli society, in terms of education, citizenship, national service and other aspects.[21][needs update][22][better source needed]

| Part of a series on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict |

| Israeli–Palestinian peace process |

|---|

Etymology

On 27 June 1967, Israel expanded the municipal boundaries of West Jerusalem so as to include approximately 70 km2 (27.0 sq mi) of West Bank territory today referred to as East Jerusalem, which included Jordanian East Jerusalem (6 km2 (1,500 acres)) and 28 villages and areas of the Bethlehem and Beit Jala municipalities 64 km2 (25 sq mi).[23][24][25]

East Jerusalem is the familiar term in English. Arabs largely use the term Arab Jerusalem for this area in official English-language documents, emphasizing the predominance of the Arabic-speaking Palestinian population while Israelis call the area East Jerusalem because of its geographic location in the east of the expanded Jerusalem.[26]

History

Ancient period

The area of East Jerusalem has been inhabited since 5000 BCE, with settlement beginning in the Chalcolithic period. Tombs are attested by the Early Bronze Age, around 3200 BCE. In the late second millennium BCE settlement concentrated around the City of David which was chosen because of its proximity to the Gihon Spring. Massive Canaanite constructions were undertaken, with a water channel excavated through rock drawing water to a pool inside the citadel, whose wall was a massive 23 feet thick, built from rocks some weighing up to 3 tons.[28][29]

British Mandatory Period

In 1934, the British Mandatory authorities divided Jerusalem into 12 wards for electoral purposes. The mapping was criticized by those who believed it was drawn to ensure a Palestinian majority on the Jerusalem city council. The actual mapping suggests otherwise, according to Michael Dumper, who states that the peculiar "hook" on the western electoral borders was a gerrymander made to include as many new Jewish neighbourhoods on that side as possible, while keeping outside of the boundaries Arab villages. To the east, the city's border ended at the Old City walls, in order to exclude the contiguous Arab neighbourhood of Silwan, Ras al-Amud and At-Tur and Abu Tor. These boundaries defined the municipality down to 1948.[30] By 1947 Palestinian Arabs constituted a majority overall in the Jerusalem district, but Jews predominated within the British municipal boundaries, 99,000 to 65,100 Arabs.[31] The Jewish presence in eastern Jerusalem was concentrated to the Old Quarter, with a scattering also present in Silwan and Sheikh Jarrah.[32]

1948 Arab–Israeli War and aftermath

Of the 30 holy places in Jerusalem, only three were located in Western Jerusalem, with the overwhelming bulk lying within the eastern sector.[33] During the subsequent 1948 Arab–Israeli War, a large number of Jerusalem's churches, convents, mosques, synagogues, monasteries and cemeteries were hit by shell or gunfire.[34] After the armistice the city was divided into two parts. The western portion came under Israeli rule, while the eastern portion, populated mainly by Muslim and Christian Palestinians, came under Jordanian rule, with the international community withholding recognition of the respective areas of control of both parties.[35]

During the Battle for Jerusalem, fighting in the Jewish quarter between the Jordanian Arab Legion and the IDF, Irgun and Lehi had been particularly fierce, leaving the zone in ruins. The battle and subsequent looting by Palestinian civilians left 27 synagogues and 30 schools destroyed.[36] The Jordanian army is said to have blown up, three days after conquering the area, what remained of the Hurva Synagogue, which had served both as a civilian refuge and Israeli military post.[36]

For Palestinians, expulsions from the Jerusalem area date back to January 1948, when the Haganah bombed the Semiramis Hotel in Qatamon. The death of 26 civilians marked the beginning of evacuation of the area, which increased after the nearby Deir Yassin massacre in early April, followed by a 3-day assault and looting from 30 April onwards.[37] In the first six months of the 1948 war 6,000 Jews also abandoned the city, and when war broke out, thousands fled the northern areas subject to Jordanian shelling. After the surrender to the Jordanian Arab Legion, the Red Cross, which had been invested with the authority to protect many major sites,[d] oversaw the evacuation westwards through Zion Gate of some 1,300 Jews from the Old Quarter.[39] The only eastern area of the city that remained in Israeli hands throughout the 19 years of Jordanian rule was Mount Scopus, where the Hebrew University is located, which formed an enclave during that period. Likewise, Palestinians[e] living in such western Jerusalem neighbourhoods as Qatamon, Talbiya, Baq'a, 'Ayn Karim, Lifta[41] and Malha either fled or were forced out,[f] many of them seeking refuge in the Old City.[38]

East Jerusalem absorbed thousands of Palestinian refugees, a substantial number of whom were middle-class people[43] from West Jerusalem's Arab neighborhoods when they came under Israeli rule, and many were settled in the previous Jewish areas of the eastern sector,[44] whose inhabitants, likewise refugees, were relocated in the formerly majority-Arab suburbs of West Jerusalem, such as Overall; as a result of the conflict, the Jewish population of Jerusalem fell by 30–40%, while Eyal Benvenisti states half of its Palestinian population of 60,000 left. According to the Jordanian census of 1952, East Jerusalem had an Arab population of 46,700.[45]

Jordanian rule

Jerusalem was to be an international city under the 1947 UN Partition Plan. It was not included as a part of either the proposed Jewish or Arab states. During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the western part of Jerusalem was captured by Israel, while East Jerusalem (including the Old City) was captured by Jordan. The war came to an end with the signing of the 1949 Armistice Agreements.[44] On 23 January 1950, Israel declared Jerusalem its capital, with a Knesset resolution declaring that, "With the creation of a Jewish State, Jerusalem again became its capital".[46] Jordan followed suit on 24 April and, on the basis of a referendum conducted also among Palestinian West Bankers, the Hashemite Kingdom incorporated the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. The unification was recognized by the United Kingdom, which however stipulated that they did not recognize the assertion of Jordanian sovereignty over East Jerusalem, but only de facto control. The United States, while approving the unification, withheld making any public statement and likewise affirmed that since the issue of Jerusalem was sub judice, it did not recognize either the Israeli annexation of West Jerusalem, nor the Jordanian annexation of the eastern area of the city.[47]

The municipal boundaries of Jordanian East Jerusalem were expanded to cover 6 square kilometres (2.3 sq mi) by taking in the nearby villages of Silwan, Ras al-Amud Aqabat al-Suwana, 'Ard al-Samar and parts of Shuafat.[48][49] This expansion of the boundaries was prompted in large part by the need to cope with housing the refugee flow of Palestinians from West Jerusalem.[50] While many municipal functions were shifted to Amman, in 1953, Jordan conferred on East Jerusalem the status of amana (trusteeship)- in response to Israel efforts to make West Jerusalem Israel's capital- effectively making the city Jordan's second capital. The political motive behind the transfer of the bureaucracy to Amman lay in the desire to weaken the power of the rival al-Husayni family.[48]

Generally, the Jordanian authorities maintained the Ottoman status quo with regard to sacred sites in East Jerusalem. When the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, always an object of bitter contention between Greek Orthodox and Latin Christians, was engulfed in flames and severely damaged on 29 November 1949, the Vatican proposed the Tesla plan, which foresaw a reconstruction involving the demolition of the existing church and a contiguous mosque and its replacement by a predominantly Catholic-style structure. Jordan's King Abdullah gave his assent, on one condition he knew would be impossible to fulfill and therefore would abort the project. He stipulated that to go ahead, all involved denominations would have to approve the plan, which would have given the Catholic Church a primacy of authority over the others. Repairs were delayed a decade until a consensus was achieved between the Greek, Latin, and Armenian clerics (excluding the Copts), with Jordan playing a pivotal role as mediator.[51]

In the early 1960s, Jordan gave the go-ahead for the construction of the Intercontinental Hotel on the Mount of Olives on waqf terrain expropriated in 1952 from the family of Abd al-Razzaq al-'Alami.[52] Three roads, one an access route built through the Jewish Har HaZeitim Cemetery damaged many gravestones, though opinions differ as to the scale of the damage. For Yitzhak Reiter, the majority of graves were unaffected. According to Michael Fischbach, 40,000 of the 50,000 tombstones suffered some form of desecration.[36] The Israeli government protested the desecration, stating that some gravestones had been used for roadwork and a military latrine.[g][h] This East Jerusalem controversy inverted the terms of an earlier dispute when Jordan complained in 1950 of Israeli damage to the Mamilla cemetery in West Jerusalem.[52][i]

Tourism in Palestine had long been an undeveloped and marginal sector of the local economy, and, with the division of Jerusalem after 1948, political issues impeded its commercial development as a tourist destination.[56] Eastern Jerusalem suffered an outflow of population, partially accounted for by merchants and administrators moving to Amman.[citation needed] On the other hand, it maintained its religious importance, as well as its role as a regional center. Reaffirming a 1953 statement, Jordan in 1960 declared Jerusalem its second capital.[57] The US (and other powers) protested this plan, and stated it could not "recognize or associate itself in any way with actions which confer upon Jerusalem the attributes of a seat of government..."[58]

During the 1960s, Jerusalem saw economic improvement and its tourism industry developed significantly, and its holy sites attracted growing numbers of pilgrims, but as Jordan did not recognize Israeli passports, neither Jewish nor Muslim Israelis were allowed access to their traditional sites of worship in East Jerusalem, though Israeli Christians, with a special laissez-passer. were permitted to visit Bethlehem over Christmas and the New Year.[59][60]

Israeli rule

After 1967 war

Following the 1967 Six-Day War, the eastern part of Jerusalem came under Israeli rule, along with the entire West Bank. Shortly after the Israeli takeover, East Jerusalem was absorbed into West Jerusalem, together with several neighboring West Bank villages. In November 1967, United Nations Security Council Resolution 242 was passed, calling for Israel to withdraw "from territories occupied in the recent conflict" in exchange for peace treaties. In 1980, the Knesset passed the Jerusalem Law, which declared that "Jerusalem, complete and united, is the capital of Israel", which is commonly called an act of annexation, though no such formal measure was taken.[61][62] This declaration was determined to be "null and void" by United Nations Security Council Resolution 478.

David Ben-Gurion presented his party's assertion that "Jewish Jerusalem is an organic, inseparable part of the State of Israel" in December 1949,[63] and Jordan annexed East Jerusalem the following year.[64][48] These decisions were confirmed respectively in the Israeli Knesset in January 1950 and the Jordanian Parliament in April 1950.[65] When occupied by Israel after the 1967 Six-Day War, East Jerusalem, with expanded borders, came under direct Israeli rule, an effective de facto annexation.[j] In a unanimous General Assembly resolution, the United Nations declared the measures changing the status of the city to be invalid.[68]

In the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO)'s Palestinian Declaration of Independence of 1988, Jerusalem is stated to be the capital of the State of Palestine. In 2000, the Palestinian Authority passed a law proclaiming Jerusalem as its capital, and in October 2002, this law was approved by chairman Yasser Arafat.[69] Since that time Israel has shut down all offices and NGO organisations connected to the PLO in East Jerusalem, saying that the Oslo Accords do not permit the Palestinian National Authority to operate in Jerusalem.[k] The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) recognised East Jerusalem as capital of the State of Palestine on 13 December 2017.[71]

Overview

On 28 June 1967, Israel extended Israeli "law, jurisdiction and administration" to the area of East Jerusalem, without naming it, by incorporating it into its municipality of West Jerusalem.[72] Internally, this move was explained as one of annexation, integrating that part of the city into Israel. Towards the international community, which was critical, it was justified as a purely technical measure, to provide equal administrative services to all its residents, and not annexation, and the same applied to Israel's assertion of a claim of sovereignty on the passage of the 30 July 1980 Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel.[l][72][74] The United Nations Security Council censured Israel for the move and declared the law "null and void" in United Nations Security Council Resolution 478, and the international community continues to regard East Jerusalem as held under Israeli occupation.[75][76] Israel then disbanded the elected Arab municipal council placing it under the administration of West Jerusalem's mayor Teddy Kollek.

A problem arose when it was noted that East Jerusalem also had a mayor, Ruhi al-Khatib, and an elected 11 other members on the Jordanian city council. Uzi Narkiss realized the Arab council had not been dismissed. He therefore ordered the deputy military governor, Ya'akov Salman, to depose the council. Salman was at a loss as to how this measure could be executed, but Narkiss insisted he find some grounds for doing so. Eventually, Salman summoned Khatib and 4 other members to the Gloria Hotel restaurant, and read out a short statement in Hebrew.[77]

In the name of the Israeli Defense Forces, I respectfully inform Mr Ruhi al-Khatib and members of the Jerusalem City Council that the Council is hereby dissolved.[78]

al-Khatib demanded the order in writing, and an Arabic translation was written out on a napkin. According to Uzi Benzamin, the Israeli journalist who wrote up the encounter, "the whole episode lacked any shred of legality".[79] Soon after al-Khatib, who had worked for an orderly transition, was deported to Jordan for organizing protests.[m][80]

Services like electricity supply were transferred from Palestinian to Israeli companies, and a ministerial decision established a policy that the ratio of Jews to Palestinians, as a matter of policy, would be 76 to 24,[81] though the 2000 Masterplan adjusted this to a 70-30 ratio, which in turn had to be subject to a 60-40% proportion given Palestinian demographic growth, which now constitutes 37% of the city's population.[82] When offered a path to Israeli citizenship, the overwhelming majority opted for resident status instead, and adopted a boycott strategy against Israeli institutions.[83][n] 90% of the land of East Jerusalem included thereafter in its municipality was added after 1967 by expropriating in most cases village or private land owned by people who were living in 28 Palestinian villages. According to its former deputy mayor, Meron Benvenisti, the plan was designed in such a way as to incorporate a maximum of land with a minimum of Arabs.[84][o] Thereafter, a property tax (arnona) regime was introduced which allowed Jewish settlers a 5-year exemption and then reduced taxes, while leaving Jerusalemite West Bankers, whose zones are classified to be in the high-property-tax bracket, paying for 26% of municipal services, while themselves receiving only 5% of the benefit (2000).[86] By 1986, 60% of Arab East Jerusalem lacked a garbage-collection infrastructure, and schools could not expand classrooms and were forced into a unique double-shift system.[87] Jewish neighbourhoods were allowed to build up to eight storeys high, while Palestinians in East Jerusalem were restricted to two.[88] The area's infrastructure still remains in a state of neglect.[p] According to B'Tselem, as of 2017, the 370,000 overcrowded West Bankers in this zone are bereft of any control over their lives, given extreme restrictions on the movement of residents without any advance notice. Their residency can be revoked; building permits are rarely given and a separation wall fences them off from the rest of the city. Every day 140,000 Palestinians have to negotiate checkpoints to work, get a medical check-up or visit friends.[90] Poverty has steadily increased among them, with 77% of "non-Jewish" households in Jerusalem under the Israeli poverty line, as opposed to 24.4% of Jewish families (2010).[91]

An International Crisis Group report of 2012 described the effects of Israeli policies: cut off from trade with the West Bank by the Separation Barrier, denied political organization – which Israel's counter-terrorism agency includes as "political subversion" – by the closure of the PLO's Orient House, it is an "orphan city" hemmed in by flourishing Jewish neighbourhoods. With local construction blocked, the Palestinian neighbourhoods have become slums, where even the Israeli police will not venture except for security reasons, so that criminal businesses have thrived.[92]

Territorial modifications

The extension of Israeli jurisdiction into East Jerusalem and its surroundings on into the municipality of Jerusalem involved the inclusion of several neighboring villages, expanding the municipality area of Jordanian East Jerusalem by integrating into it a further 111 km2 (43 sq mi) of West Bank territory,[93][94] while excluding many of East Jerusalem's suburbs, such as Abu Dis, Al-Eizariya, Beit Hanina and Al-Ram,[95] and dividing several Arab villages. Israel refrained however from endowing citizenship – a mark of annexation — on the Palestinians incorporated within the new municipal borders.[96]

The old Mughrabi Quarter in front of the Western Wall was bulldozed three days after its capture, leading to the forced resettlement of its 135 families.[94][97] It was replaced with a large open-air plaza. The Jewish Quarter, destroyed in 1948, was depopulated, rebuilt and resettled by Jews.[94]

After 1980 incorporation

Under Israeli rule, members of all religions are largely granted access to their holy sites, with the Muslim Waqf maintaining control of the Temple Mount and the Muslim holy sites there.

With the stated purpose of preventing infiltration during the Second Intifada, Israel decided to surround Jerusalem's eastern perimeter with a security barrier. The structure has separated East Jerusalem neighborhoods from the West Bank suburbs, all of which are under the jurisdiction of Israel and the IDF. The planned route of the separation barrier has raised much criticism, with the Israeli Supreme Court ruling that certain sections of the barrier (including East Jerusalem sections) must be re-routed.[citation needed]

In the Oslo Accords, the PLO conceded that the question of East Jerusalem be excluded from the interim agreement, and be left to final status negotiations.[98] Under the pretext that they are part of the PA, Israel closed many Palestinian NGOs since 2001.[70]

At the 25 January 2006 Palestinian Legislative Elections, 6,300 East Jerusalem Arabs were registered and permitted to vote locally. All other residents had to travel to West Bank polling stations. Hamas won four seats and Fatah two, even though Hamas was barred by Israel from campaigning in the city. Fewer than 6,000 residents were permitted to vote locally in the prior 1996 elections.[citation needed]

In March 2009, a confidential "EU Heads of Mission Report on East Jerusalem" was published, in which the Israeli government was accused of "actively pursuing the illegal annexation" of East Jerusalem. The report stated: "Israeli 'facts on the ground' – including new settlements, construction of the barrier, discriminatory housing policies, house demolitions, restrictive permit regime and continued closure of Palestinian institutions – increase Jewish Israeli presence in East Jerusalem, weaken the Palestinian community in the city, impede Palestinian urban development and separate East Jerusalem from the rest of the West Bank."[99]

In 2018, Al Bawaba reported that Israel had approved the construction of 640 new "Jewish-only" housing units in the ultra-orthodox Ramat Shlomo settlement.[100] Some of these units will be built on privately owned Palestinian lands.[101] According to B'tselem, the Israeli authorities have destroyed 949 Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem since 2004, resulting in the displacement of over 3,000 Palestinians. Since 2016 there has been a notable uptick in demolitions, with 92 razed that year. In the first ten months of 2019 over 140 homes were demolished, leaving 238 Palestinians, 127 of them minors, homeless.[102][103]

A poll among East Jerusalem Arab residents in 2011, conducted by the Palestinian Center for Public Opinion and American Pechter Middle East Polls for the Council on Foreign Relations, revealed that 39% of East Jerusalem Arab residents would prefer Israeli citizenship contrary to 31% who opted for Palestinian citizenship. According to the poll, 40% of Palestinian residents would prefer to leave their neighborhoods if they would be placed under Palestinian rule.[104]

As of 1998, Jerusalem's religious heritage consists of 1,072 synagogues, 52 mosques, 65 churches and 72 monasteries.[33]

Status

Sovereignty

East Jerusalem has been occupied by Israel since 1967 and has been effectively annexed, in an act internationally condemned,[by whom?] by Israel in 1980. On 27–28 June 1967, East Jerusalem was integrated into Jerusalem by extension of its municipal borders and was placed under the law, jurisdiction and administration of the State of Israel.[61] In a unanimous General Assembly resolution, the UN declared the measures trying to change the status of the city invalid.[68]

In a reply to the resolution, Israel denied these measures constituted annexation and contended that it merely wanted to deliver services to its inhabitants and protect the Holy Places.[q] Some lawyers, among them Yehuda Blum and Julius Stone, have argued that Israel has sovereignty over East Jerusalem under international law, since Jordan did not have legal sovereignty over the territory, and thus Israel was entitled in an act of self-defense during the Six-Day War to "fill the vacuum".[106][r] This interpretation is a minority position, and international law considers all the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) to be occupied territory[108] and call for Palestinians in the occupied territories (including East Jerusalem) to be given self-determination[109]

Israel has never formally annexed Jerusalem, nor claimed sovereignty there but its extension of Israeli law and administration there in 1967, and the Jerusalem Basic Law of 1980 are often taken as constituting an effective[61] or de facto annexation.[110] The Israeli Supreme Court recognized that East Jerusalem had become an integral part of the State of Israel,[61] ruling that even if Knesset laws contravene international law, the court is bound by domestic law and therefore considers the area annexed.[111] According to lawyers, the annexation of an area would automatically make its inhabitants Israeli citizens,[61] a condition lacking and East Jerusalem's Palestinians have the status of "permanent residents". The United Nations General Assembly resolution 67/19 of 2012 affirmed that East Jerusalem forms a part of Occupied Palestine Territory.

Historically, defining a Palestinian position on Jerusalem and East Jerusalem proved difficult, given the political conflicts that arose between strategies proposed by the local East Jerusalemite establishment led by Faisal Husseini and those of the PLO under Yasser Arafat regarding the processes to be chosen to define the city's Palestinian status.[112]

Negotiations on "share" or "divide"

Both the Oslo Accords and the 2003 Road map for peace postponed the negotiations on the status of Jerusalem. The 1997 Beilin–Eitan Agreement between some members of the Likud block and Yossi Beilin, representing Labor, which envisioned for final negotiations a limited autonomy to a demilitarized "Palestinian entity" surrounded on all sides by Israel, stated that all of Jerusalem would remain unified under Israeli sovereignty. Beilin suggested Palestinians would accept a capital outside of Jerusalem in Abu Dis, which undermined the credibility of the document in Palestinian eyes.[113][114][115]

Israel's settlement policy in East Jerusalem has been described by Avi Shlaim and others as one aiming to preempt negotiations by creating facts on the ground.[116]

The Beilin–Abu Mazen agreement of 1995, suggested while Israel would not accept challenges to its political sovereignty over all of Jerusalem it might, with the idea of a holy basin, theoretically allow Palestinian extraterritorial sovereignty over a part of the East Jerusalem area, with Palestinians directly controlling the Noble Sanctuary, while Jews would obtain religious rights over the Temple Mount. This view, splitting religious and political authority, was unacceptable to Hamas and Arafat soon disowned the idea.[117] At the 2000 Camp David Summit, it was agreed there could be no return to the pre-1967 Jerusalem lines of demarcation; that Israel's unilaterally imposed municipal boundaries were not fixed; that just as Israel's expansion there would be larger than mapped just after 1967, so too the Palestinian expansion would stretch out to take in villages not connected to the city earlier; that Jerusalem would remain a single unified metropolitan unit not divided by an international border, and under the governance of two distinct municipal authorities, with one under full Palestinian sovereignty and serving as the capital of the State of Palestine, exercising full powers in most parts of East Jerusalem. An exchange of neighbourhoods was envisaged, with Israel taking sovereignty over Ma'ale Adumim, Givat Ze'ev and Gush Etzion, while excluding areas earlier included, such as Sur Baher, Beit Hanina and Shu'afat.[118] During the last serious negotiations in 2008 with the government of Ehud Olmert, Olmert, on 16 September, included a map which foresaw a shared arrangement over Jerusalem, with Israeli settlements remaining in Israel and Palestinian neighbourhoods part of a Palestinian state and constituting their future capital. The Holy Basin, including the Old City, would be under joint trusteeship overseen by Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Israel, the United States and the state of Palestine. Olmert showed, but would not share, the map with Mahmood Abbas, who was forced to make a copy of it on a napkin.[119]

Jerusalem as capital

While both Israel and Palestine declared Jerusalem their capital, the Palestinians usually refer to East Jerusalem as the capital of the State of Palestine.[120]

In 1980, the Knesset adopted the "Jerusalem Law" as a Basic Law, declaring Jerusalem "complete and united", "the capital of Israel". The law applied to both West and East Jerusalem within, among others, the expanded boundaries as defined in June 1967. While the Jerusalem Law has political and symbolic importance, it added nothing to the legal or administrative circumstance of the city.[61]

The Israeli-Palestinian Declaration of Principles (Oslo I), signed 13 September 1993, deferred the settlement of the permanent status of Jerusalem to the final stages of negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians.

The Beilin-Abu Mazen Plan stated that, "Israel will recognize that the (portion of) the area defined as 'Al-Quds' prior to the six day war which exceeds the area annexed to Israel in 1967 will be the capital of the Palestinian state". This formulation was based, according to Tanya Reinhart, on a verbal trick in that, by conferring on Abu Dis, which was within the Jordanian municipality of Jerusalem but outside Israel's redefinition, the title the holy city referring in Arabic to Jerusalem, Israel could assert that it was acceding to the idea of dividing Jerusalem. Arafat concurred with this Israeli proposal, and Israel asserted a pre-condition, namely, that all Palestinian institutions be removed from Jerusalem proper and transferred to Abu Dis. In compliance, the Palestinians built their government offices and a proposed future parliament house there, but an undertaking to transfer Abu Dis, and the neighbouring Al-Eizariya into Area C, under full Palestinian autonomy, was never fulfilled. Ehud Barak had, it is reported, before the Camp David talks, reneged on this promise which was personally conveyed to the Palestinians through President Bill Clinton. Barak remained committed to a unified Israeli Jerusalem, the default position of all Israeli governments who regard its division as non-negotiable.[121]

At the Taba Summit in 2001 Israel made substantial concessions regarding territory but not sufficient to permit a contiguous Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem.[122]

Position of the United States

The United States refers to East Jerusalem as part of "the West Bank – the larger of the two Palestinian territories", and refers to Israeli Jews living in East Jerusalem as "settlers".[123]

American policy on Jerusalem, despite a standard refrain of "continuity," has been altered repeatedly since 1947, exhibiting sometimes drastic fluctuations since 1967.[124] Historically, up to 1967, it had viewed East Jerusalem as forming part of the West Bank, a territory under belligerent occupation.[125] On 1 March 1990, President George H. W. Bush stated publicly, the first time for an American president, an objection to Israeli building in East Jerusalem.[126] That same year, the United States Congress unanimously adopted the Senate's Concurrent Resolution 106, affirming its belief that Jerusalem must remain an undivided city with the Senate Concurrent Resolution 113 of 1992. This was sponsored by AIPAC and, according to John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt, was a "transparent attempt to disrupt the peace process".[127] In the Jerusalem Embassy Act of 8 November 1995 it set 1999 as the final date whereby the U.S. embassy was to be relocated to that city, stating Jerusalem should be recognized as the capital of Israel, and that no more than 50% of State Department funds for building abroad should be allocated until the embassy was established there. Provision was made for the exercise of a presidential waiver.[128]

In 1991, as part of a preparatory gesture before the Madrid Peace Conference, the United States in a Letter of Assurances to the Palestinians (15 October 1991) stated that the United States undertook to act as an honest broker and expressed opposition to any unilateral measures that might prejudice peace talks, a statement the Palestinians understood to refer to Israeli settlements and policy in Jerusalem.[129] Nevertheless, the subsequent Clinton Administration refused to characterize East Jerusalem as being under occupation and viewed it as a territory over which sovereignty was undefined.[125] Vice President Al Gore stated that the U.S. viewed "united Jerusalem" as the capital of Israel. In 2016, U.S. presidential election candidate Donald Trump vowed to recognize all of Jerusalem as the undivided capital of Israel if he won the election.[130] In 2017, President Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital, and, on 14 May 2018, the United States moved its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.[131] On 8 December 2017, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson clarified that the President's statement "did not indicate any final status for Jerusalem" and "was very clear that the final status, including the borders, would be left to the two parties to negotiate and decide."[132]

When U.S. President Joe Biden visited Israel and Palestine in 2022, his delegation removed the Israeli flags from his vehicle upon entering East Jerusalem, in a move widely interpreted as signaling non recognition of Israeli sovereignty over East Jerusalem.[133]

Urban planning

The term East Jerusalem sometimes refers to the area which was incorporated into the municipality of Jerusalem after 1967, covering some 70 km2 (27 sq mi), while sometimes it refers to the smaller area of the pre-1967 Jordanian-controlled part of the Jerusalem municipality, covering 6.4 km2 (2.5 sq mi). 39 percent (372,000) of Jerusalem's 800,000 residents are Palestinian, but the municipal budget allocates only 10% of its budget to them.[134]

East Jerusalem has been designed to become an Israeli Jewish city surrounding numerous small enclaves, under military control, for the Palestinian residents.[135] The last link in the chain of settlements closing off East Jerusalem from the West Bank was forged in 1997 when Binyamin Netanyahu approved, as part of what he perceived as a battle for the city, the construction of the settlement of Har Homa.[s]

According to the Israeli non-governmental organization B'Tselem, since the 1990s, policies that made construction permits harder to obtain for Arab residents have caused a housing shortage that forces many of them to seek housing outside East Jerusalem.[136] East Jerusalem residents that are married to residents of the West Bank and Gaza have had to leave Jerusalem to join their husbands and wives due to the citizenship law. Many have left Jerusalem in search of work abroad, as, in the aftermath of the Second Intifada, East Jerusalem has increasingly been cut off from the West Bank and thereby has lost its main economic hub. Israeli journalist Shahar Shahar argues that this outmigration has led many Palestinians in East Jerusalem to lose their permanent residency status.[137]

According to the American Friends Service Committee and Marshall J. Breger, such restrictions on Palestinian planning and development in East Jerusalem are part of Israel's policy of promoting a Jewish majority in the city.[138][139]

On 13 May 2007, the Israeli Cabinet began a discussion regarding a proposal to expand Israel's presence in East Jerusalem and boost its economy so as to attract Jewish settlers. To facilitate more Jewish settlement in East Jerusalem, the Cabinet is now considering an approximately 5.75 billion NIS plan to reduce taxes in the area, relocate a range of governmental offices, construct new courthouses, and build a new center for Jerusalem studies. Plans to construct 25,000 Jewish homes in East Jerusalem are in the development stages. As Arab residents are hard-pressed to obtain building permits to develop existing infrastructure or housing in East Jerusalem, this proposition has received much criticism.[140][141]

According to Justus Weiner of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, the Jerusalem municipality granted the Arab sector 36,000 building permits, "more than enough to meet the needs of Arab residents through legal construction until 2020". Both Arabs and Jews "typically wait 4–6 weeks for permit approval, enjoy a similar rate of application approvals, and pay an identical fee ($3,600) for water and sewage hook-ups on the same size living unit". Weiner writes that while illegal Jewish construction typically involves additions to existing legal structures, illegal Arab construction involves the construction of entire multi-floor buildings with 4 to 25 living units, built with financial assistance from the Palestinian National Authority on land not owned by the builder.[142]

A European Union report of March 2010 has asserted that 93,000 East Jerusalem Palestinians, 33% of the total, are at risk of losing their homes, given Israeli building restrictions imposed on them, with only 13% of the municipal territory allowed for their housing, as opposed to 53% for Jewish settlement. It wrote further that in 2013 98 such buildings were demolished, leaving 298 people homeless, while a further 400 lost their workplace and livelihoods, and that 80% live below the poverty level. 2,000 Palestinian children, and 250 teachers in the sector must pass Israeli checkpoints to get to school each day.[134]

Jewish neighbourhoods in East Jerusalem have 30 times the number of playgrounds that Palestinian areas have. One was built for the 40,000 strong community of Sur Baher with Belgian funding in 2015 after a Jerusalem court directed the municipal council to begin constructing them. It was constructed without a permit, and the Israeli authorities say the difference is due to the difficulty of finding vacant lots suitable to playgrounds in the Arab sectors.[143]

The annual number of building permits granted for construction in Israeli settlements in East Jerusalem have expanded by 60% since Donald Trump became US president in 2017. Since 1991, Palestinians, who make up the majority of the residents in East Jerusalem, have only received 30% of building permits.[144]

In 2021, Israel's Supreme Court had been expected to deliver a ruling on 10 May 2021 on whether to uphold the eviction of Palestinian families from the Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood that had been permitted by a lower court.[145] In May 2021, clashes between Palestinians and Israeli police occurred over the anticipated evictions.[146]

Demographics

In the 1967 census, the Israeli authorities registered 66,000 Palestinian residents (44,000 residing in the area known before the 1967 war as East Jerusalem; and 22,000, in the West Bank area annexed to Jerusalem after the war). Only a few hundred Jews were living in East Jerusalem at that time, since most Jews had been expelled in 1948 during the Jordanian rule.[147]

By June 1993, a Jewish majority was established in East Jerusalem: 155,000 Jews were officially registered residents, as compared to 150,000 Palestinians.[148]

At the end of 2008, the population of East Jerusalem was 456,300, comprising 60% of Jerusalem's residents. Of these, 195,500 (43%) were Jews, (comprising 40% of the Jewish population of Jerusalem as a whole), and 260,800 (57%) were Arabs. Of the Arabs, 95% were Muslims, comprising 98% of the Muslim population of Jerusalem, and the remaining 5% were Christians.[149] In 2008, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics reported the number of Palestinians living in East Jerusalem was 208,000 according to a recently completed census.[150]

At the end of 2008, East Jerusalem's main Arab neighborhoods included Shuafat (38,800), Beit Hanina (27,900), the Muslim Quarter of the Old City (26,300), At-Tur including As-Sawana (24,400). East Jerusalem's main Jewish neighborhoods include Ramot (42,200), Pisgat Ze'ev (42,100), Gilo (26,900), Neve Yaakov (20,400), Ramat Shlomo (15,100) and East Talpiot (12,200). The Old City (including the already mentioned Muslim Quarter) has an Arab population of 36,681 and a Jewish population of 3,847.[151]

In 2016, the population of East Jerusalem was 542,400, comprising 61% of Jerusalem's residents. Of these, 214,600 (39.6%) were Jews, and 327,700 (60.4%) were Arabs.[152]

According to Peace Now, approvals for building in Israeli settlements in East Jerusalem has expanded by 60% since Trump became US president in 2017.[153] Since 1991, Palestinians who make up the majority of the residents in the area have only received 30% of the building permits.[154]

Among the Arab neighborhoods of East Jerusalem, the northern neighborhoods tend to be wealthy, while the southeastern neighborhoods are home to a poorer population whose origins are more often rural or tribal. Many of the wealthier Arabs have moved there from northern Israel. About half of Jerusalem Arabs, though, have their ancestry in the Hebron region.[155]

Residency and citizenship

This section needs to be updated. (July 2022) |

Following the 1967 war, Israel conducted a census in East Jerusalem and granted permanent Israeli residency to those Arab Jerusalemites present at the time of the census. Those not present lost the right to reside in Jerusalem. Jerusalem Palestinians are permitted to apply for Israeli citizenship, provided they meet the requirements for naturalization—such as swearing allegiance to Israel and renouncing all other citizenships—which most of them refuse to do.[dubious – discuss] At the end of 2005, 93% of the Arab population of East Jerusalem had permanent residency and 5% had Israeli citizenship.[156]

Between 2008 and 2010, approximately 4,500 Palestinian residents in East Jerusalem applied for Israeli citizenship, of which one third were accepted, one third rejected, and one third had the decision postponed.[157]

As residents, East Jerusalemites without Israeli citizenship have the right to vote in municipal elections and play a role in the administration of the city. Residents pay taxes, and following a 1988 Israeli Supreme Court ruling, East Jerusalem residents are guaranteed the right to social security benefits and state health care. Until 1995, those who lived abroad for more than seven years or obtained residency or citizenship in another country were deemed liable to lose their residency status. In 1995, Israel began revoking permanent residency status from former Arab residents of Jerusalem who could not prove that their "center of life" was still in Jerusalem. This policy was rescinded four years later. In March 2000, the Minister of the Interior, Natan Sharansky, stated that the "quiet deportation" policy would cease, the prior policy would be restored, and Arab natives to Jerusalem would be able to regain residency[90] if they could prove that they have visited Israel at least once every three years. Since December 1995, permanent residency of more than 3,000 individuals "expired", leaving them with neither citizenship nor residency.[90] Despite changes in policy under Sharansky, in 2006 the number of former Arab Jerusalemites to lose their residency status was 1,363, a sixfold increase on the year before.[158]

Over 95% of East Jerusalemite Palestinians retain residency status rather than citizenship. Application for citizenship have grown from 69 (2003) to over 1,000 (2018) but obtaining Israel citizenship has been described as an uphill battle, with the number of applicants who receive a positive response meager. Obtaining an appointment for an interview alone can take 3 years followed by another 3 to 4 years to obtain a decision one way or another. Of 1,081 requests in 2016 only 7 were approved, though by 2018, 353 approvals were given to the 1,012 Palestinians applying. Lack of sufficient fluency in Hebrew, suspicions the applicant might have property in the West Bank, or be a security risk (such as having once visited a relative gaoled on security grounds) are considered impediments.[159]

East Jerusalem residents are increasingly becoming integrated into Israeli society. Trends among East Jerusalem residents have shown: increasing numbers of applications for an Israeli ID card; more high school students taking the Israeli matriculation exams; greater numbers enrolling in Israeli academic institutions; a decline in the birthrate; more requests for building permits; a rising number of East Jerusalem youth volunteering for national service; a higher level of satisfaction according to polls of residents; increased Israeli health services; and a survey showing that in a final agreement more East Jerusalem Palestinians would prefer to remain under Israeli rule.[21] According to Middle East expert David Pollock, in the hypothesis that a final agreement was reached between Israel and the Palestinians with the establishment of a two-state solution, 48% of East Jerusalem Arabs would prefer being citizens of Israel, while 42% of them would prefer the State of Palestine. 9% would prefer Jordanian citizenship.[160]

Healthcare

Until 1998, residents of East Jerusalem were disadvantaged in terms of healthcare service and providers. By 2012, almost every neighborhood in East Jerusalem had health clinics that included advanced medical equipment, specialized ER units, X-ray diagnostic centers and dental clinics.[21] Israel's system of healthcare entitles all Israeli citizens and East Jerusalem residents to receive free healthcare service funded by the Israeli government.

According to Haaretz in 2015, the quality of healthcare centers between Israeli cities and East Jerusalem are almost equal. The health quality indices in East Jerusalem increased from a grade of 74 in 2009 to 87 in 2012, which is the same quality grade the clinics in West Jerusalem received.[21]B'tselem maintains that, despite constituting 40% of Jerusalem's population, the municipality only runs six healthcare centers in the Palestinian sector, compared to the 27 run by the state in Jewish neighbourhoods.[103] According to ACRI, only 11% of the residents of East Jerusalem are treated by the welfare services. In 2006 64% of the Palestinian population lived below the poverty line. By 2015 75%, and 84% of their children, were living below the poverty line.[161]

In 2018, President Donald Trump's administration cut $25 million from hospitals in East Jerusalem that specialized in cancer care for Palestinians.[162] The cut in funds covers 40% of the running costs for 6 hospitals providing treatment for patients from both the Gaza Strip and the broader West Bank where treatment is unavailable. The shortfall was thought to put at serious risk the viability of both Augusta Victoria Hospital and Saint John Eye Hospital. The sum saved was to be redirected to "high-priority projects" elsewhere.[163]

Culture

Jerusalem was designated the Arab Capital of Culture in 2009.[164][165] In March 2009, Israel's Internal Security Minister responded with a number of injunctions, banning scheduled cultural events in the framework of this designation in Jerusalem, Nazareth and in other parts of the Palestinian Territories. The Minister instructed Israel Police to "suppress any attempts by the PA to hold events in Jerusalem and throughout the rest of the country". The minister issued the ban on the basis that the events would be a violation of a clause in the interim agreement between Israel and the Palestinians that forbids the Palestinian Authority (PA) from organizing events in Israeli territory.[166]

On 22 June 2013, the Israeli Public Security Minister closed the El-Hakawati Theater for eight days, to prevent a puppet theater festival with an 18-year tradition. Israel Security Agency Shin Bet accused the Palestinian Authority of funding the child-festival, which was denied by the theater director.[167] A month later, members of Israel's theater world held a protest.[168]

On 29 June 2013, Israel denied members of the Ramallah Orchestra from the Al Kamandjâti music school access to East Jerusalem, where they were to give a concert in the French St. Anne's church. Nevertheless, after the musicians had climbed over the Separation Wall, the concert eventually took place.[169][170]

Environment

East Jerusalem has been recognised as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because its walls and old buildings provide nesting sites for a population of lesser kestrels, with some 35–40 breeding pairs estimated in 1991. The city, especially the Mount of Olives region, also underlies a white stork migration route.[171]

Economy

May 2013, UNCTAD published the first comprehensive investigation into the East Jerusalem economy undertaken by the United Nations.[172] The report concluded that the Israeli occupation had caused the economy to shrink by half in the last 20 years compared to West Bank and Gaza Strip, which it described as "a dismal testament to the decline of the East Jerusalem economy and its growing isolation under prolonged occupation", that resulted in the economic isolation of Palestinian residents.[172][173] It found a 77% to 25% differential in the number of households living below the poverty line in non-Jewish and Jewish households respectively, with the differential in child poverty being 84% for Palestinian children as opposed to 45% for Jewish children.[172][173] Major problems were said to be restrictions on movement of goods and people, which Israel says are imposed for security reasons, and Israeli neglect of "dire socio-economic conditions".[172][173] UNCTAD said "the Israeli government could go much further in meeting its obligations as an occupying power by acting with vigour to improve the economic conditions in East Jerusalem and the well-being of its Palestinian residents".[172][173] The Palestinians' governor of Jerusalem said "some relaxation of the political situation" was required for the economy to improve.[172]

Education

According to the Israeli Education Ministry, the number of East Jerusalem high school students who took Israeli matriculation exams rose from 5,240 in 2008 to 6,022 in 2011. There are 10 schools in East Jerusalem that specialize in preparing East Jerusalem students for Israeli universities and colleges; one of the biggest schools is the Anta Ma'ana ("You are with us") Institute on Al-Zahara Street.[21]

East Jerusalem has a shortage of schools for Palestinian children. In 2012, the classroom shortage was reportedly 1,100, due to what Haaretz described as "years of intentional neglect of East Jerusalem schools, which serve the Arab population by the Education Ministry and the city". A relatively high dropout rate of schoolchildren is found in the Arab sector, even 40% among 12th graders in 2011.[174]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (March 2016) |

Schools in East Jerusalem include:

Mayors

- Anwar Khatib (1948–1950)

- Aref al-Aref (1950–1951)

- Hannah Atallah (1951–1952)

- Omar Wa'ari (1952–1955)

- Ruhi al-Khatib (1957–1967)

- Ruhi al-Khatib (1967–1994; titular)

- Amin al-Majaj (1994–1999; titular)

- Zaki al-Ghul (1999–2019; titular)[175]

See also

- Green Line

- List of East Jerusalem locations

- Quds Governorate (Jerusalem Governorate)

References

Notes

- ^ "following the war between Israel and the Palestinian and Arab states in 1948, Jerusalem was divided into an Israeli-held western sector and a Jordanian-held eastern sector."[1]

- ^ "Both states treated the respective sectors of Jerusalem under their effective control as forming an integral part of their state territory between 1948 and 1967, and each recognized the other's de facto control in their respective sectors by the signature of the 1949 Jordan-Israel General Armistice Agreement."[17]

- ^ "Israeli and Palestinian sources differ in their definition of East Jerusalem."[20]

- ^ "Such buildings included the YMCA, the King David Hotel (the around these two building constituted the international area of the Red Cross), the Government House and all the hospitals, as long as they were not used for waging war operations, like the Hadassah and others. Immediately after midnight on May 14, the Jewish army occupied all these security zones. So they occupied the Greek and German colonies, the Upper Baq'a, the Russian Compounds and the prisons, and later arrived in front of the Old City Walls. The next day, they started to pound the Old City Gates with bombs, mortar shells and rifle fire, claiming to want to take the city, but with a first priority of rescuing the almost two thousand besieged Jews inside the city, many of whom were from the Haganah organization".[38]

- ^ By Jerusalemite "Palestinians" for this period, aside from Jews, are to be understood significant communities of Armenians, Syriacs, Greeks and Ethiopians, and German Templars, the former particularly present in the Old City, but with all groups maintaining substantial holdings and residences in what became West Jerusalem.[40]

- ^ 'Zionist militias began to attack the large, middle-class Aarab suburbs in West Jerusalem. Our neighbours in Ilaret al-Nammareh started to flee the highly equipped Zionist militias who had begun advancing toward our neighbourhood. Raiding parties cut telephone and electric wires. My father heard the Zionists demand that we all leave immediately. Their loudspeaker-equipped vans drove through the streets, blaring such messages as "Unless you leave your houses, the fate of Deir Yassin will be your fate!"[42]

- ^ "The ancient Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives was ransacked: graves were desecrated: thousands of tombstones were smashed or taken away and used as building material, paving stones or, as Israel claimed, used for latrines in the Jordanian Army camps. The Intercontinental Hotel was built on top of the cemetery and graves were demolished to make a way for a road to the hotel."[53]

- ^ "Many thousand tombstones were taken from the ancient cemetery of the Mount of Olives to serve as building material or paving stones. A few were even used to serve as building material or paving stones. A few were even used to surface the footpath leading to a latrine in a Jordanian army camp. With the financial assistance of Pan American Airlines, Jordan built the Hotel Intercontinental – a plush hotel on the hill of Jesus' agony! Obviously a road was needed, worthy of the triumphant showpiece. Of all the possible routes, the one chosen cut through hundreds of Jewish graves. They were torn open and the bones scattered."[54]

- ^ "This has been a casual desecration, albeit one less well publicized than that of Jewish tombs on the Mount of Olives from 1949 until 1967, and with no overarching purpose guiding it, except perhaps that of replacing the old with the new, the Arab with the Israeli, which motivated so many actions of the Israeli state after 1948.."[55]

- ^ Although it was claimed that the application of the Israeli law to East Jerusalem was not properly annexation[61] this position was rejected by the Israeli Supreme Court. In a 1970 majority ruling, Justice Y. Kahan expressed the opinion ". . . As far as I am concerned, there is no need for any certificate from the Foreign Minister or from any administrative authority to determine that East Jerusalem. . . was annexed to the State of Israel and constitutes part of its territory. . . by means of these two enactments and consequently this area constitutes part of the territory of Israel."[66][67]

- ^ "Since 2001, Israel has shut down more than 22 Palestinian non-governmental organizations (NGOs), including charities and service centers in Jerusalem, causing increased suffering for the people of this city already struggling under Israeli occupation. This was carried out under various pretexts, most notably the claim that the agreements with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), especially the Oslo Accords, prohibit the establishment of any activity of the Palestinian Authority (PA) in Jerusalem."[70]

- ^ "In terms of internal Israeli politics, local leaders were not shy to admit that as a result of these enactments, East Jerusalem was now fully integrated within Israel. Asher Maoz aptly summarized this policy as follows: 'while the leaders of the state were making it clear both within and without the Knesset that East Jerusalem had been annexed to Israel, the representatives of the state in international forums fervently denied that this was the result.'"[73]

- ^ "The IDF did not show any consideration for the fact that al-Khatib had done much to enable an orderly transition of power. The Arab mayor had, for three weeks, taken action to reopen shops, remove debris and bodies, ensure the operation of the electrical grid and the supply of fuel, milk, and flour from the western side of the city. In radio broadcasts, he called on the city's Arabs to hand over weapons in their possession to the Israeli authorities."[77]

- ^ Of the 15,000 Palestinian Jerusalemites who have, since 2003, applied for Israeli citizenship, only 6,000 applications were approved by 2017.[82]

- ^ Levi Eshkol very early on in the occupation spoke of the need to separate the bride (the Palestinians) from the dowry (the occupied territories).[85]

- ^ "Why this disregard for the level of public services in east Jerusalem? The answer is a poorly kept secret: Arab east Jerusalem is simply at the bottom of the list of priorities of the Israeli authorities when it comes to funding public works...Whatever the label, it does not change the picture of Arab East Jerusalem as largely undeveloped and unserviced for over three decades of Israeli rule".[89]

- ^ The letter delivered to the U.N. Secretary General on July 10 reads: "The term 'annexation' used by supporters of the General Assembly's resolution of 4 July was out of place since [...] the measures adopted related to the integration of Jerusalem in the administrative and municipal spheres and furnished a legal basis for the protection of the Holy Places".[105]

- ^ "Others argued that it might lawfully retain them permanently on the theory that Jordan had not held lawful title and therefore, there was no sovereign power to whom the territories could revert. Israel, it was said - particularly because it took the territories defensively - had a better claim to title than anyone else. That argument ignored however the generally recognized proposition that uncertainty over sovereignty provides no ground to retain territory taken in hostilities. Even if Jordan held the West Bank on only a de facto basis, Israel could not, even acting in self-defense, acquire title."[107]

- ^ "Netanyahu fired the opening shot in the battle for Jerusalem on 19 February 1997 with a plan for the construction of 6,500 housing units for 30,000 Israelis at Har Homa, in annexed East Jerusalem. 'The battle for Jerusalem has begun,' he declared in mid-March as Israeli bulldozers went into action to clear the site for a Jewish neighbourhood near the Arab village of Sur Bahir. 'We are now in the thick of it, and I do not intend to lose.' Har Homa was a pine-forested hill, south of the city proper, on the road to Bethlehem. Its Arabic name is Jabal Abu Ghunaym. The site was chosen in order to complete the chain of Jewish settlements around Jerusalem and cut off contact between the Arab side of the city and its hinterland in the West Bank. It was a blatant example of the Zionist tactic of creating facts on the ground to preempt negotiations."[116]

Citations

- ^ Dumper 2002, p. 42.

- ^ "Top UN court says Israel's presence in occupied Palestinian territories is illegal and should end".

- ^ "The Illegality of the Israeli Occupation of the Palestinian West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and Gaza: What the International Court of Justice Will Have to Determine in its Advisory Opinion for the United Nations General Assembly". Opinio Juris. 23 December 2022. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "East Jerusalem - OCHA" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Topônimos e gentílicos - Manual de Redação - FUNAG". funag.gov.br. Archived from the original on 28 January 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ China supports Palestinian UN bid (Xinhua, 8 September 2011) Archived 16 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine "China recognizes Palestine as a country with east Jerusalem as its capital and possessing full sovereignty and independence, in accordance with borders agreed upon in 1967, according to Jiang"

- ^ Medvedev reaffirms Soviet recognition of Palestine (Ynet News, 18 January 2011) Archived 26 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine "Russian president says Moscow has not changed its position since 1988 when it 'recognized independent Palestinian state with its capital in east Jerusalem'"

- ^ Muslim leaders urge world to recognise East Jerusalem as capital of Palestine (France 24, 2017-12-13) Archived 27 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine "their final statement declared "East Jerusalem as the capital of the State of Palestine" and invited "all countries to recognise the State of Palestine and East Jerusalem as its occupied capital.""

- ^ "Finland's country strategy for Palestine - 2021-2024". Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Australia recognises west Jerusalem as capital of Israel". France 24. 15 December 2018. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Ministère de l'Europe et des Affaires étrangères. "Israel / Palestinian Territories – France condemns the expulsion of Mr Salah Hamouri (18 Dec. 2022)". France Diplomacy - Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Jerusalem Institute - 2022" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Israel", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 21 December 2022, archived from the original on 10 January 2021, retrieved 2 January 2023

- ^ Utenriksdepartementet (18 January 2010). "Norge bekymret over situasjonen i Øst-Jerusalem". Regjeringen.no (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Israel approves new settler homes". BBC News. 5 April 2011. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ Hasson 2000, pp. 15–24.

- ^ Korman 1996, p. 251.

- ^ "Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 30 July 1980. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- ^ Leigh Phillips (19 November 2009). "EU rebukes Israel for Jerusalem settlement expansion" Archived 22 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine. EUObserver. "The issue of Jerusalem is one of the most intractable issues in the Israel-Palestine conflict. While both Israelis and Palestinians claim Jerusalem as their capital, most countries maintain their embassies in Tel Aviv while the occupied territories are administered by the Palestinian Authority in the town of Ramallah."

- ^ Farsakh 2005, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Hasson 2012.

- ^ Koren, David (13 September 2018). "The desire of eastern Jerusalem Arabs to integrate in Israeli society outweighs the threats of the Palestinian Authority". JISS. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Holzman-Gazit 2016, p. 134, n.11.

- ^ Schmidt 2008, p. 340.

- ^ Lustick 1997, pp. 35, 37.

- ^ Klein 2001, p. 7.

- ^ Elisha Efrat and Allen G. Noble, Planning Jerusalem Archived 6 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Geographical Review, Vol. 78, No. 4 (Oct., 1988), pp. 387-404: "Modern planning began only after the British conquest of Palestine in World War I… In 1918 an engineer from Alexandria, William McLean, was commissioned to draft the first city plan… These provisions… caused the city to develop mainly to the west and southwest because of the restrictions on construction in the Old City and its immediate environs and the desire to retain the eastern skyline… McLean wanted Jerusalem to expand to the north, west, and south, with little development to the east because of climatic and topographical limitations. Thus almost from the onset of British colonial rule, development was encouraged in a generally westward direction, and this bias ultimately produced the initial contrasts that distinguished the eastern and western sectors of the city. McLean also adopted the principle of urban dispersal, and he proposed two main axes, one to the northwest and the other to the southwest of the Old City. His guidelines were repeated in most of the subsequent city plans."

- ^ Montefiore 2011, p. 18.

- ^ Ussishkin 2003, p. 105.

- ^ Dumper 1997, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Tamari 2010, p. 94.

- ^ Dumper 2014, p. 273 n.66.

- ^ a b Berkovitz 1998, pp. 405–406.

- ^ Israeli 2014, p. 171.

- ^ Dumper 2014, p. 51.

- ^ a b c Fischbach 2008, p. 86.

- ^ Tamari 2010, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b Tamari 2010, p. 99.

- ^ Naor 2013, p. 153.

- ^ Tamari 2010, p. 96.

- ^ Tamari 2010, p. 97.

- ^ Nammar 2012.

- ^ Tamari 2010, pp. 94ff.

- ^ a b Israeli 2014, p. 118.

- ^ Dumper 2014, p. 46.

- ^ Slonim 1998, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Slonim 1998, pp. 176, 182–183.

- ^ a b c Dumper 1997, p. 33.

- ^ Dumper 2014, p. 47.

- ^ Dumper 2014, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Reiter 2017, pp. 55–58.

- ^ a b Reiter 2017, p. 179,n.13.

- ^ Balfour 2019, p. 162.

- ^ Millgram 1990, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Khalidi 1992, p. 140.

- ^ Isaac, Hall & Higgins-Desbiolles 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Bovis 1971, p. 99.

- ^ Lapidoth & Hirsch 1994, p. 160.

- ^ Israeli 2014, pp. 23, 118, 197.

- ^ Breger & Hammer 2010, p. 49, n.168.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lustick 1997, pp. 34–45.

- ^ Dinstein 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Hulme 2006, p. 94.

- ^ Klein 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Korman 1996, p. 251,n.5.

- ^ Ofra Friesel (May 2016). "Israel's 1967 Governmental Debate about the Annexation of East Jerusalem: The Nascent Alliance with the United States, Overshadowed by "United Jerusalem"". Law and History Review. 34 (2): 363–391. doi:10.1017/S0738248016000031. ISSN 0738-2480. S2CID 146933736.

- ^ Dumper 2014, pp. 50–51, 63–64.

- ^ a b UNGA 2253 1997, p. 151.

- ^ Cohen 2013, p. 70.

- ^ a b Hirbawi & Helfand 2011.

- ^ OIC 2017.

- ^ a b Benvenisti & Zamir 1995, p. 307.

- ^ Karayanni 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Benvenisti 2012, p. 204.

- ^ Benvenisti 2012, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Dumper 2010, p. 119.

- ^ a b Klein 2014, p. 155.

- ^ Gorenberg 2007, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Talhami 2017, p. 110.

- ^ Mattar 2005, p. 269.

- ^ Malki 2000, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b HRW 2017b.

- ^ ICG 2012, pp. I–ii.

- ^ Makdisi 2010, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Handel 2010, p. 266.

- ^ Malki 2000, p. 34.

- ^ Cheshin, Hutman & Melamed 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Ziai 2013, p. 137.

- ^ Cheshin, Hutman & Melamed 2009, pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b c B'Tselem 2017a.

- ^ UNCTAD 2013, p. 96.

- ^ ICG 2012, pp. i–ii, 1.

- ^ Segal 2003, p. 185.

- ^ a b c Hiltermann 1995.

- ^ Dumper 2014, p. 49.

- ^ Dumper 2014, p. 50.

- ^ Gorenberg 2007, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Weinberger 2007, p. 85.

- ^ McCarthy 2009.

- ^ Al Bawaba 2018.

- ^ Hasson & Khoury 2018.

- ^ Yumna Patel, 'Israel destroyed record number of Palestinian homes in Jerusalem in 2019,' Archived 27 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine Mondoweiss 25 October 2019

- ^ a b 'Demolition of houses and Non-residential structures in East Jerusalem, 2004-2019,' Archived 25 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine B'tselem 24 October 2019

- ^ Benhorin 2011.

- ^ Cohen 1985, p. 39.

- ^ Stone 2004.

- ^ Quigley 2005, p. 173.

- ^ United Nations News Centre 2012.

- ^ Palestine–Israel Journal 1997.

- ^ Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel (December 2013). The Legal Status of East Jerusalem (PDF) (Report). Norwegian Refugee Council. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

In the wake of the 1967 war, Israel applied its "law, jurisdiction and administration" to a significant part of the West Bank, which is known as "East Jerusalem". Israel has mostly refrained from describing these acts as "annexation" or declaring that this legislation constitutes an act of acquisition of sovereignty. Yet, with the passage of time, additional pieces of legislation, introduced by Israel, in addition to extensive Israeli measures on the ground, in particular the expansion of the settlements, have left little doubt about Israel's intentions. The de facto annexation has grown stronger and deepened.

- ^ Dinstein 2009, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Klein 2014, pp. 183–204.

- ^ Eriksson 2013, p. 221.

- ^ Chiller-Glaus 2007, pp. 157–158.

- ^ McMahon 2010, pp. 109–110, 128.

- ^ a b Shlaim 2015, p. 581.

- ^ Goddard 2010, p. 206.

- ^ Klein 2001, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Kurtzer et al. 2012, p. 231.

- ^ United Nations 2007.

- ^ Reinhart 2011, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Mattar 2005, p. 477.

- ^ "West Bank", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 21 December 2022, archived from the original on 22 July 2021, retrieved 3 January 2023

- ^ Slonim 1998, pp. 359–360.

- ^ a b Bowen 1997, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Slonim 1998, p. 359, n.1.

- ^ Mearsheimer & Walt 2007, p. 127.

- ^ Slonim 1998, pp. 377–381.

- ^ Kurtzer et al. 2012, p. 56.

- ^ Hanna, Andrew; Saba, Yousef (15 December 2017). "Will Trump move the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem?". Politico. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ Davis, Julie Hirschfeld (15 May 2018). "Jerusalem Embassy Is a Victory for Trump, and a Complication for Middle East Peace". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ Morello, Carol (8 December 2017). "U.S. Embassy's move to Jerusalem should take at least two years, Tillerson says". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ "Biden visits east Jerusalem without Israeli flag on limousine". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 15 July 2022. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ a b Hass 2014.

- ^ Dumper 2014, pp. 16, 69, 92.

- ^ B'Tselem 2017b.

- ^ Shahar 2007.

- ^ AFSC 2004.

- ^ Breger 1997.

- ^ BBC News 2007.

- ^ Reuters 2007.

- ^ Weiner n.d.

- ^ ToI 2016.

- ^ "New data shows Israeli settlement surge in east Jerusalem". Ynetnews. 9 December 2019. Archived from the original on 12 September 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ "Explainer: Jerusalem tense over evictions and holidays". Reuters. 10 May 2021. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Scores injured in fresh night of Jerusalem clashes". The Guardian. 9 May 2021. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Totten 2011.

- ^ The Realization of Economic 1994.

- ^ Choshen & Korach 2010.

- ^ The Jerusalem Post 2008.

- ^ Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies 2010.

- ^ JIPR 2018.

- ^ "New data shows Israeli settlement surge in east Jerusalem". AP. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 13 September 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "New data shows Israeli settlement surge in east Jerusalem". Ynetnews. Ynetnews.com. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 12 September 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ "Who are the Arabs of Jerusalem?". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 10 February 2022. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ ICBoS 2007.

- ^ Hasson 2013.

- ^ The Economist 2007.

- ^ Hasson 2019.

- ^ "New Poll Reveals Moderate Trend Among East Jerusalem Palestinians". The Washington Institute. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ ACRI 2015.

- ^ Tibon 2019.

- ^ Shahar 2018.

- ^ Capitals of Arab Culture 2009.

- ^ Ma'an 2009.

- ^ Hass 2013.

- ^ Haaretz 2013.

- ^ Tolan 2013a.

- ^ Tolan 2013b.

- ^ "Jerusalem (east)". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Browning 2013.

- ^ a b c d UNCTAD 2013.

- ^ Kashti 2012.

- ^ Reiter, Yitzhak (1 March 2011). "King Solomon's Vanishing Temple". The American Interest. Vol. 6, no. 4. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

Sources

- Balfour, Alan (2019). The Walls of Jerusalem: Preserving the Past, Controlling the Future. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-18229-0. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- Benhorin, Yitzhak (13 January 2011). "Jerusalem Arabs prefer Israel; US poll: 39% of east Jerusalem Arabs prefer to live under Israeli sovereignty; 30% didn't answer". Ynetnews.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Benvenisti, Eyal; Zamir, Eyal (April 1995). "Private Claims to Property Rights in the Future Israeli-Palestinian Settlement". The American Journal of International Law. 89 (2): 295–340. doi:10.2307/2204205. JSTOR 2204205. S2CID 145317224.

- Benvenisti, Eyal (2012). The International Law of Occupation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-58889-3. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Berkovitz, Shmuel (July–September 1998). "The Holy Places in Jerusalem: Legal Aspects". Rivista di Studi Politici Internazionali. 65 (3): 403–415. JSTOR 42739221.

- Bovis, H. Eugene (1971). The Jerusalem Question, 1917–1968. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8179-3291-6. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Bowen, Stephen (1997). Human rights, self-determination and political change in the occupied Palestinian territories. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-90-411-0502-8. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- Breger, Marshall J. (March 1997). "Understanding Jerusalem". Middle East Quarterly. Archived from the original on 9 February 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- Breger, Marshall J.; Hammer, Leonard (2010). "The legal regulation of holy sites". In Breger, Marshall J.; Reiter, Yitzhak; Hammer, Leonard (eds.). Holy Places in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Confrontation and Co-existence. Routledge. pp. 20–49. ISBN 978-1-135-26812-1. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- Bregman, Ahron (2002). Israel's Wars: A History Since 1947. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-28716-6.

- Browning, Noah (9 May 2013). "Israeli occupation sapping East Jerusalem economy – U.N. report". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- "B'Tselem – Revocation of Residency in East Jerusalem". B'Tselem. 11 November 2017a. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- "East Jerusalem". B'Tselem. 27 January 2019. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "A capital question: More Palestinians are losing their right to live in Jerusalem than ever before". The Economist. 10 May 2007. Archived from the original on 15 May 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- "Capitals of Arab Culture Jerusalem". 2009. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Cheshin, Amir; Hutman, Bill; Melamed, Avi (2009). Separate and Unequal. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02952-1. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- Chiller-Glaus, Michael (2007). Tackling the Intractable: Palestinian Refugees and the Search for Middle East Peace. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-039-11298-2. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Choshen, Maya; Korach, Michal (2010). "Jerusalem, Facts and Trends 2009–2010" (PDF). Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- Cohen, Esther Rosalind (1985). Human rights in the Israeli-occupied territories, 1967–1982. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-1726-1. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2018.