The Wolf Man (1941 film)

| The Wolf Man | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | George Waggner |

| Written by | Curt Siodmak |

| Produced by | George Waggner |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Joseph Valentine |

| Edited by | Ted J. Kent |

| Music by | |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 70 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $180,000[1] |

The Wolf Man is a 1941 American gothic horror film written by Curt Siodmak and produced and directed by George Waggner. The film stars Lon Chaney Jr. in the title role. Claude Rains, Warren William, Ralph Bellamy, Patric Knowles, Bela Lugosi, Evelyn Ankers, and Maria Ouspenskaya star in supporting roles. The title character has had a great deal of influence on Hollywood's depictions of the legend of the werewolf.[2] The film is the second Universal Pictures werewolf film, preceded six years earlier by the less commercially successful Werewolf of London (1935). This film is one of the Universal Monsters movies, and garnered great acclaim for its production.

After this movie's success, Lon Chaney Jr. would reprise his role as "The Wolf Man" in four sequels, beginning with Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man in 1943.

Plot

[edit]Larry Talbot returns to his ancestral home in Llanwelly, Wales, to bury his recently deceased brother and reconcile with his estranged father, Sir John Talbot. Larry falls in love with a local girl named Gwen Conliffe who runs an antique shop. As an excuse to talk to her, he purchases a walking stick decorated with a silver wolf's head. Gwen tells him that it represents a werewolf, a man who changes into a wolf "at certain times of the year". The werewolf always sees a pentagram on the palm of his next victim. Various villagers recite a poem whenever werewolves are mentioned.

Though Gwen firmly refuses Larry's persistent proposals for a date, they meet that night at the proposed time, and are joined by Gwen's friend Jenny to go have their fortunes told. The Romani fortuneteller, Bela, sees a pentagram when he examines Jenny's palm, and frantically sends her away. While awaiting their turns, Larry and Gwen take a walk. Gwen informs Larry that she is engaged. They hear screams from Jenny, who is being attacked by a wolf. Larry attempts to rescue Jenny. He kills the wolf with his new walking stick but is bitten on the chest. Police investigating the scene find Jenny's throat torn out and Bela battered to death, with Larry's walking stick clearly the murder weapon in the latter case. Suspicion on Larry deepens when he cannot substantiate his story of fighting a wolf, since his chest wound miraculously healed overnight. The fact that Larry and Gwen were not with Jenny when she was attacked additionally raises suspicions of adultery. Though Gwen's fiance Frank believes in their innocence, Larry and Gwen become local pariahs.

Bela's mother, Maleva, reveals to Larry that the wolf which bit him was Bela in the form of a wolf, and Larry is now a werewolf too because he was bitten by one. Silver is the only thing that can kill a werewolf. Maleva gives him a charm to prevent the transformation. Uncertain whether or not to believe her, he instead gives the charm to Gwen for protection.

Like Maleva warned, Larry transforms into a humanoid wolf hybrid on the following night and kills a villager. He returns to normal the next morning with no memory of his rampage. Authorities believe the killing to be the work of a wolf; they set traps and send out hunting parties. The next night, Larry turns into a werewolf and is caught in one of the traps. Maleva uses a spell to temporarily change him back to human form, allowing him to free himself before a hunting party finds him.

Now convinced he is a werewolf, a distraught Larry decides to leave town. When he says his goodbye to Gwen, he sees a pentagram on her palm. He tells his father he is a werewolf and killed Bela and the villager, but his father thinks Larry is delusional and ties him to a chair to prevent him from leaving and prove to him he is not a werewolf. When the moon rises Larry transforms again, breaks free of his restraints, and attacks Gwen. Not recognizing the werewolf as his son, Sir John bludgeons him over the head with Larry's silver-headed cane which Larry gave him. Maleva arrives and again uses the spell. Sir John watches in horror as the dead werewolf transforms into Larry's human corpse.

Cast

[edit]

- Lon Chaney Jr. as Lawrence "Larry" Talbot / The Wolf Man

- Claude Rains as Sir John Talbot

- Warren William as Dr. Lloyd

- Ralph Bellamy as Captain Paul Montford (opening credits show Colonel Montford)

- Patric Knowles as Frank Andrews

- Bela Lugosi as Bela, the Romani fortune teller and werewolf

- Maria Ouspenskaya as Maleva, the Romani sorceress

- Evelyn Ankers as Gwen Conliffe

- J. M. Kerrigan as Charles Conliffe

- Fay Helm as Jenny Williams

- Forrester Harvey as Twiddle

- Doris Lloyd as Mrs. Williams, Jenny's Mother

- Harry Stubbs as Reverend Norman

Themes and interpretations

[edit]In an essay for the 1984 book Planks of Reason, academic Bruce F. Kawin wrote that, "The Wolf Man expresses and exorcises the Id-force of uncontrolled aggression in its own system (the werewolf), in Larry Talbot (his werewolf phases), and in the community (the destabilizing forces of rape, murder, gypsy liminality, and aristocratic privilege—Talbot often behaves as if he had droit du seigneur when courting the engaged Gwen)."[3] In 1995, author Edmund G. Bansak compared Talbot's "blindly aggressive drive" in his romantic pursuit of the Welsh Gwen to that of Oliver Reed, a character played by Kent Smith in the 1942 film Cat People who courts the Serbian-born Irene Dubrovna (Simone Simon): "neither of these stereotypical All-American males will take no for an answer."[4]

As with other werewolf films, The Wolf Man has been analyzed as an allegory for puberty.[5] In his 2012 book Horror and the Horror Film, Kawin wrote: "The fear of sexual passion and its ability to bring chaos is part of the arsenal of anxiety inherent to puberty, and the werewolf does, as has been widely noted, grow hair and become subject to animalistic drives as if it were going through puberty. In The Wolf Man (1941) as well as in Cat People (1942), desire is dangerous. The monster is one's animal nature, out of control and making one behave like an animal."[6]

In 1993, film historian David J. Skal characterized The Wolf Man and its sequels as reflecting the anxieties of American audiences amidst World War II, calling the series "an unconscious parable of the war effort" that centers around Talbot's "crusade for eternal peace and his frustrated attempts to control irrational, violent European forces."[7] In his 2004 book Nightmares in Red, White and Blue, Joseph Maddrey wrote that the resolution of The Wolf Man "is not reassuring in the way that earlier Universal horror films, with their distinctly Manichean view of the world, were. Larry Talbot is not torn between forces of good and evil; he is a victim of a cruel or indifferent fate in a less comprehensible world."[8]

Production

[edit]

Special effects makeup

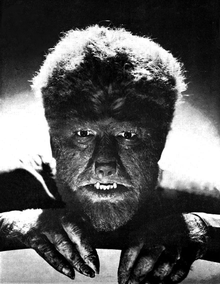

[edit]Chaney did not undergo an on-screen facial transformation from man to wolf in the original film, as featured in all sequels. The lap-dissolve progressive makeups were seen only in the final ten minutes and were presented discreetly. In the first transformation, Larry removes his shoes and socks. His feet are seen to grow hairy and become huge paws (courtesy of uncomfortable "boots" made of hard rubber, covered in yak hair). In the final scene, the werewolf gradually returns to Larry Talbot's human form through the standard technique.

Application process

[edit]Stories about the makeup and transformation scenes have become legendary and are mostly apocryphal. The transformation of Chaney from man into a monster was certainly laborious; the entirety of the makeup took five to six hours to apply and an hour to remove.[9] Jack Pierce had initially designed it for Henry Hull in Werewolf of London (1935), but Hull argued that the disguise made no sense within the plot since "Dr. Glendon" needed to be recognizable by the characters even in his werewolf form. Pierce was ordered to design a second version which left more of Hull's face recognizable. Pierce then recycled his original design for the 1941 film.

Chaney claimed he was forced to sit motionless for hours as the scenes were shot frame by frame. At times he claimed he was left to remain sitting while the crew broke for lunch and was also equivocal about using the bathroom. Chaney even said special effects men drove tiny finishing nails into the skin on the sides of his hands so they would remain motionless during close-ups.[citation needed]

However, studio logs indicate that during the filming of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), the entire crew, including Chaney, took a two-hour break during the filming of a transformation and filmed the rest of the scene later that day (though the makeup for Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein had significantly been redesigned and streamlined by Bud Westmore over the original Jack Pierce makeup). A plaster mold was made to hold his head still, as his image was photographed and his outline drawn on panes of glass in front of the camera. Chaney then went to makeup man Jack Pierce's department, where Pierce, using grease paint, a rubber snout appliance, and a series of wigs, glued layers of yak hair to Chaney's face. Then Chaney would return to the set, line himself up using the panes of glass as a reference, and several feet of film was shot. Then Chaney would return to the makeup department. A new layer would be applied to show the transformation being further along. He would then return to the sound stage to film. This was done about a half-dozen times. Talbot's lap dissolve transformation on screen only took seconds, while Chaney's took almost ten hours.

Reception

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 91% based on 43 reviews, with an average rating of 7.8/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "A handsomely told tale with an affecting performance from Lon Chaney, Jr., The Wolf Man remains one of the classics of the Universal horror stable."[10] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 72 out of 100, based on eight critics, indicating "generally favorable" reviews.[11]

Author and film critic Leonard Maltin awarded the film 3.5 out of 4 stars, calling it "one of the finest horror films ever made". Maltin praised the film's makeup effects, atmospheric music, and Chaney's performance in his review.[12]

Home media

[edit]In the early 1990s, MCA/Universal Home Video released The Wolf Man on VHS as part of the "Universal Monsters Classic Collection".[13]

In 1999, Universal released The Wolf Man on VHS and DVD as part of the "Classic Monster Collection", a series of releases of Universal Classic Monsters films.[14][15][16] On April 27, 2004, Universal released The Wolf Man: The Legacy Collection on DVD as part of the "Universal Legacy Collection".[17][18] This two-disc release includes The Wolf Man, along with Werewolf of London, Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, and She-Wolf of London.[17][18] In 2009, Universal digitally remastered and re-released The Wolf Man on DVD as a two-disc "Special Edition", as part of the "Universal Legacy Series".[19][20] In 2012, The Wolf Man was released on Blu-ray as part of the Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection box set, which includes a total of nine films from the Universal Classic Monsters series.[21][22]

In 2013, The Wolf Man received a standalone Blu-ray release.[23][24] In 2014, Universal released The Wolf Man: Complete Legacy Collection on DVD.[25] This set contains seven films: The Wolf Man, Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, The House of Frankenstein, House of Dracula, Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, Werewolf of London, and She-Wolf of London.[25] In 2016, the seven-film Complete Legacy Collection was released on Blu-ray.[26] That same year, The Wolf Man received a Walmart-exclusive Blu-ray release featuring a glow-in-the-dark cover.[27] In September 2017, the film received a Best Buy-exclusive SteelBook Blu-ray release with cover artwork by Alex Ross.[28]

The Wolf Man was included in the Universal Classic Monsters: Complete 30-Film Collection Blu-ray box set in August 2018.[29][30] This box set also received a DVD release.[31] In October the same year, the film was included as part of a limited edition Best Buy-exclusive Blu-ray set titled Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection, which features artwork by Alex Ross.[32] Universal Pictures Home Entertainment released The Wolf Man on 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray on October 5, 2021.[33]

Legacy

[edit]The Wolf Man is the only Universal monster to be played by the same actor in all his 1940s film appearances. Lon Chaney Jr. was very proud of this, frequently stating in interviews that the Wolf Man was his 'baby'.[34] The Wolf Man is listed in the film reference book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, which stated that the film 'remains the most recognizable and most cherished version of the [werewolf] myth'.[35]

The Wolf Man is one of three top-tier Universal Studios monsters without a direct literary source. The others are The Mummy and the Creature from the Black Lagoon. In the 1970s, novelizations of the original films were issued as paperback originals as part of a series written by "Carl Dreadstone", a pseudonym for British horror writer Ramsey Campbell.[36]

Sequels

[edit]The Wolf Man proved popular, so Chaney reprised his signature role in four more Universal films. However, unlike his contemporary "monsters", Larry Talbot never had a sequel all to himself. Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943) had Talbot's grave opened on a full moon night, causing him to rise again (making him, in the subsequent films, technically one of the undead). The full moon, which had not been shown or mentioned in the first film, was used as a quasi-explanation for the monster's resurrection, and the poem known to the local villagers was retconned to mention the full moon so that the last line became "and the moon is full and bright."

The resurrected Talbot seeks out Dr. Frankenstein for a cure but finds the monster (Bela Lugosi) instead. The two square off at the climax, but the fight ends in a draw when a dam is exploded, and Frankenstein's castle is flooded. In 1944 Universal wanted to pair Dracula and the Wolf Man in "The Wolf Man vs. Dracula", but it was canceled in favor of a remake of Phantom of the Opera.[citation needed] In House of Frankenstein (1944), Talbot is once again resurrected and is promised a cure via a brain transplant but is shot dead with a silver bullet instead. He returns with no explanation in House of Dracula (1945). He is finally cured of his condition, but he is afflicted once again, in the comedy film Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948). This time the Wolf Man is a hero of sorts, saving Wilbur Grey (Lou Costello) from having his brain transplanted by Dracula (Bela Lugosi) into the head of the Monster (Glenn Strange). Grabbing the vampire as he turns into a bat, the Wolf Man dives over a balcony into the sea, taking Dracula with him.[37]

Remake

[edit]Universal Pictures produced a remake of The Wolf Man with Joe Johnston directing the film and Benicio del Toro starring as Lawrence Talbot (also producer of the film). The remake followed the same basic plot as the original. However, the story and characters were significantly altered, with Anthony Hopkins in a radically altered version of the Claude Rains role. The film was released on February 12, 2010, and opened at No. 2 at the box office that weekend. The film was met with mixed reviews and a low box office reception but won an Academy Award for Best Makeup in 2011.

Due to the 2010 remake performing below expectations at the box office, Universal chose not to produce a sequel. Universal's 2012 film Werewolf: The Beast Among Us was originally planned as a spin-off from The Wolfman but was ultimately unrelated.[38]

Reboot

[edit]Universal announced that it would reboot their Universal Monsters properties as part of their Dark Universe, with Alex Kurtzman and Chris Morgan attached to develop the structure of the shared universe.[39] In November 2014, Universal hired Aaron Guzikowski to write the shared universe's reboot of The Wolf Man.[40][41] In June 2016, Dwayne Johnson was reported to star as the character.[42] Later in October, David Callaham was brought on board to re-write the script.[43] The following year on November 8 however, Alex Kurtzman and Chris Morgan moved on to other projects, leaving the future of the Dark Universe in doubt.[44]

In May 2020, Ryan Gosling had been cast as Wolf Man for an upcoming reboot of the titular character. Lauren Shuker Blum and Rebecca Angelo co-wrote the script from an original story pitched by Gosling. The actor has previously been in negotiations to also serve as the director, but was ultimately decided that he would instead focus entirely on acting. Universal is actively pursuing a director.[45] By July, Leigh Whannell entered early negotiations to direct the project, with Jason Blum announced as an additional producer.[46] In October 2021, Deadline reported that Derek Cianfrance will write and direct the reboot.[47] On December 13, 2023, it was confirmed that Whannell was back as a director, taking Cianfrance's place, and that Christopher Abbott was cast as the main character, replacing Gosling who will remain as the executive producer. The film is scheduled to be released on January 17, 2025.[48]

Notes

[edit]The poem mentioned more than once in the film was not, contrary to popular belief, an ancient legend, but was in fact an invention of screenwriter Siodmak.[49] "Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night / can become a wolf when the wolfsbane blooms and the Autumn moon is bright." The poem is repeated in every subsequent film in which Talbot/The Wolf Man appears including the film Van Helsing with the only exceptions being House of Dracula and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. The later films change the last line of the poem to "And the moon is full and bright", and in episode 944 of Dark Shadows, Christopher Pennock (as Jeb Hawkes) recites this version of the poem.

References

[edit]- ^ Michael Brunas, John Brunas & Tom Weaver, Universal Horrors: The Studios Classic Films, 1931-46, McFarland, 1990 p267

- ^ "The Wolf Man: Classic Monster Collection (1941)". www.dvdmg.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-09. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- ^ Kawin, Bruce F. (1996). "The Mummy's Pool". In Grant, Barry Keith (ed.). Planks of Reason (Reprint ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-8108-2156-7.

- ^ Bansak, Edmund G. (2003). Fearing the Dark: The Val Lewton Career (Reprint ed.). McFarland & Company. p. 139. ISBN 0-7864-1709-9. Archived from the original on 2024-04-29.

- ^ Douglas, Adam (1993). The Beast Within: A History of the Werewolf. Avon Books. p. 306. ISBN 0-380-72264-X.

- ^ Kawin, Bruce F. (2012). Horror and the Horror Film. Anthem Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-85728-449-5.

- ^ Skal, David J. (1993). The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror. Faber and Faber. p. 217.

- ^ Maddrey, Joseph (2004). Nightmares in Red, White and Blue: The Evolution of the American Horror Film. McFarland & Company. p. 22. ISBN 0-7864-1860-5.

- ^ Vieira, p. 97

- ^ "The Wolf Man (1941) - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes.com. Flixer. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ "The Wolf Man". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ^ Leonard Maltin (3 September 2013). Leonard Maltin's 2014 Movie Guide. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 1572. ISBN 978-1-101-60955-2.

- ^ "The Wolf Man (Universal Monsters Classic Collection) [VHS]". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ The Wolf Man (Classic Monster Collection) [VHS]. ASIN 6300183092.

- ^ "The Wolf Man (Classic Monster Collection) [DVD]". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2002. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ Arrington, Chuck (May 4, 2000). "The Wolfman-1941". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Wolf Man - The Legacy Collection (The Wolf Man / Werewolf of London / Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man / She-Wolf of London) [DVD]". Amazon.com. 27 April 2004. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Erickson, Glenn (May 5, 2004). "The Wolf Man - The Legacy Collection". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Wolf Man (Special Edition) [DVD]". Amazon.com. 2 February 2010. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ Felix, Justin (February 10, 2010). "The Wolf Man". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection [Blu-ray]". Amazon.com. 2 October 2012. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "The Wolf Man [Blu-ray]". Amazon.com. 17 September 2013. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Wolf Man Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Wolf Man: Complete Legacy Collection [DVD]". Amazon.com. 2 September 2014. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Wolf Man: Complete Legacy Collection [Blu-ray]". Amazon.com. 13 September 2016. Archived from the original on October 14, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ Squires, John (September 13, 2016). "Walmart Releases Universal Monsters Classics With Glow-In-Dark Covers!". iHorror.com. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ Squires, John (June 27, 2017). "Best Buy Getting Universal Monsters Steelbooks With Stunning Alex Ross Art". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Universal Classic Monsters: Complete 30-Film Collection [Blu-ray]". Amazon.com. 28 August 2018. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "Universal Classic Monsters: Complete 30-Film Collection Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "Classic Monsters (Complete 30-Film Collection) [DVD]". Amazon.com. 2 September 2014. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ Vorel, Jim (August 3, 2021). "The Universal Monsters Are Creeping to 4K UHD for the First Time". Paste Magazine. Archived from the original on August 3, 2022. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ "DIAL B for BLOG - THE WORld's GREATEST COMIC BLOGAZINE". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ^ Steven Jay Schneider (2013). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die. Barron's. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-7641-6613-6.

- ^ Dreastone, Carl (1977). The Wolfman. New York, NY: Berkley Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0425034460.

- ^ Eggertsen, Chris (February 1, 2010). "A Look Back at a Hairy Franchise: The Transformation of 'The Wolf Man' Films". Archived from the original on October 11, 2020. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ "Werewolf: The Beast Among Us Blu-ray Review - IGN". October 2012. Archived from the original on 2020-10-12. Retrieved 2020-10-08 – via www.ign.com.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (July 16, 2014). "Universal Taps Alex Kurtzman, Chris Morgan To Relaunch Classic Movie Monster Franchises". Deadline. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (November 12, 2014). "Will Justin Lin Rev 'Fast & Furious' Finale?". Deadline. Archived from the original on May 28, 2020. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (November 12, 2014). "Sony Confirms 'Dark Matter'; Universal Confirms Aaron Guzikowski To Write 'Wolfman'". Deadline. Archived from the original on September 25, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (June 22, 2016). "Dwayne Johnson Sets Jay Longino Graphic Novel 'Son Of Shaolin' At Sony". Deadline. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (October 13, 2016). "Universal Taps 'The Expendables' Writer to Pen 'The Wolf Man' (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 14, 2016. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ Kit, Borys; Couch, Aaron (November 8, 2017). "Universal's "Monsterverse" in Peril as Top Producers Exit (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (May 29, 2020). "Ryan Gosling's 'Wolfman' Gears Up at Universal as Director Decision Nears (EXCLUSIVE)". Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (2020-07-08). "Ryan Gosling's 'Wolfman' Howling At Universal As Director Leigh Whannell & Blumhouse Join The Pack". Deadline. Archived from the original on 2020-09-18. Retrieved 2020-07-08.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (October 26, 2021). "Ryan Gosling And Universal's 'Wolfman' Sets Derek Cianfrance As Director". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ Kit, Borys (October 13, 2021). "Christopher Abbott Replacing Ryan Gosling to Star in 'Wolf Man' for Blumhouse, Universal (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 13, 2023. Retrieved December 14, 2023.

- ^ Vieira, Mark A. (2003). Hollywood Horror: From Gothic to Cosmic. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. p. 98. ISBN 0-8109-4535-5.

External links

[edit]- 1941 films

- 1941 horror films

- American black-and-white films

- Films directed by George Waggner

- Films set in Wales

- Universal Pictures films

- American werewolf films

- Films with screenplays by Curt Siodmak

- Films about filicide

- Films scored by Frank Skinner

- Films about Romani people

- Gothic horror films

- 1940s English-language films

- 1940s American films

- Films about father–son relationships

- The Wolf Man (franchise)

- English-language horror films

- Saturn Award–winning films