Philander C. Knox

Philander C. Knox | |

|---|---|

Knox in 1904 | |

| United States Senator from Pennsylvania | |

| In office March 4, 1917 – October 12, 1921 | |

| Preceded by | George T. Oliver |

| Succeeded by | William E. Crow |

| In office June 10, 1904 – March 4, 1909 | |

| Preceded by | Matthew Quay |

| Succeeded by | George T. Oliver |

| 40th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 6, 1909 – March 5, 1913 | |

| President | William Howard Taft Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | Robert Bacon |

| Succeeded by | William Jennings Bryan |

| 44th United States Attorney General | |

| In office April 5, 1901 – June 30, 1904 | |

| President | William McKinley Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | John W. Griggs |

| Succeeded by | William Moody |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Philander Chase Knox May 6, 1853 Brownsville, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | October 12, 1921 (aged 68) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Education | West Virginia University, Morgantown University of Mount Union (BA) |

| Signature |  |

Philander Chase Knox (May 6, 1853 – October 12, 1921) was an American lawyer, bank director, statesman and Republican Party politician. He represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1904 to 1909 and 1917 to 1921. He was the 44th United States Attorney General in the cabinet of William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt from 1901 to 1904 and the 40th United States Secretary of State in the cabinet of William Howard Taft from 1909 to 1913.

Born in Brownsville, Pennsylvania, Knox became a prominent attorney in Pittsburgh, forming the law firm of Knox and Reed. With the industrialists Henry Clay Frick and Andrew Mellon, Knox also served as a director of the Pittsburgh National Bank of Commerce.[1] In early 1901, he accepted appointment as United States Attorney General. Knox served under President William McKinley until McKinley was assassinated in September 1901, and Knox continued to serve under President Theodore Roosevelt until 1904, when he resigned to accept appointment to the Senate.

Knox won re-election to the Senate in 1905 and unsuccessfully sought the 1908 Republican presidential nomination. In 1909, President William Howard Taft appointed Knox to the position of United States Secretary of State. From that post, Knox reorganized the State Department and pursued dollar diplomacy, which focused on encouraging and protecting U.S. investments abroad. Knox returned to private practice in 1913 after Taft lost re-election. He won election to the Senate in 1916 and played a role in the Senate's rejection of the Treaty of Versailles. Knox was widely seen as a potential compromise candidate at the 1920 Republican National Convention, but the party's presidential nomination instead went to Warren G. Harding. While still serving in the Senate, Knox died in October 1921.

Early life, education, and marriage

[edit]

Philander Chase Knox was born in Brownsville, Pennsylvania, one of nine children of Rebecca (née Page) and David S. Knox, a banker.[2] He was named after the Episcopal Bishop Philander Chase. He attended public school in Brownsville, graduating at the age of 15.[3] He attended West Virginia University for a time, and then Mount Union College, where he graduated in 1872 with a bachelor of arts degree. While there, he formed a lifelong friendship with William McKinley, the future U.S. president, who at the time was a local district attorney. Knox then returned to Brownsville, and was occupied for a short while as a printer at the local newspaper, then as a clerk at the bank where his recently deceased father had worked. Soon he left for Pittsburgh, and studied law while working at the law offices of H. R. Swope & David Reed in Pittsburgh.[4]

Marriage and family

[edit]

In 1880, Knox married Lillian "Lillie" Smith, the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Darsie Smith. Her father was a partner in a steel company known as Smith, Sutton and Co. The company eventually became a part of Crucible Steel. Knox and his wife had several children, including Hugh Knox. His extended relatives include a nephew, "Billy" Knox. [citation needed]

Legal career

[edit]Knox was admitted to the bar in 1875 and practiced in Pittsburgh. From 1876 to 1877, he was Assistant United States Attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania. Knox became a leading Pittsburgh attorney in partnership with James Hay Reed, their firm being Knox and Reed (now Reed Smith LLP). In 1897 Knox became President of the Pennsylvania Bar Association. Along with Jesse H. Lippencott, a fellow member of an elite hunting club (see South Fork below), Knox served as a director of the Fifth National Bank of Pittsburgh. With Henry Clay Frick and Andrew Mellon, he was a director of the Pittsburgh National Bank of Commerce. As counsel for the Carnegie Steel Company, Knox took a prominent part in organizing the United States Steel Corporation in 1901. [citation needed]

Johnstown Flood

[edit]Knox was a member of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, which had a clubhouse upriver of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. It maintained an earthen dam for a lake by the club, which was stocked for fishing. The dam failed in May 1889, causing the Johnstown Flood and severe losses of life and property downriver. When word of the dam's failure was telegraphed to Pittsburgh, Frick and other members of the South Fork Club gathered to form the Pittsburgh Relief Committee for assistance to the flood victims.[citation needed]

As its attorneys; Knox and his law partner Reed were able to fend off four lawsuits against the club; Colonel Unger, its president; and against 50 named members. The cases were "either settled or discontinued and, as far as is known, no one bringing action profited thereby."[5]

The club was never held legally responsible for the disaster. Knox and Reed successfully argued that the dam's failure was a natural disaster which was an Act of God, and no legal compensation was paid to the survivors of the flood.[5] The perceived injustice aided the acceptance of “strict, joint, and several liability,” so that a “non-negligent defendant could be held liable for damage caused by the unnatural use of land.[6][7]

Political career

[edit]U.S. Attorney General

[edit]

In 1901, Knox was appointed as US Attorney General by President William McKinley and was re-appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt. He served until 1904. While serving President Roosevelt, Knox worked hard to implement the concept of Dollar Diplomacy.

He told President Roosevelt: "I think, it would be better to keep your action free from any taint of legality,"[8] made in regard to the construction of the Panama Canal.

U.S. Senator

[edit]In June 1904, Knox was appointed by Governor Samuel W. Pennypacker of Pennsylvania to fill the unexpired term of the late Matthew S. Quay in the United States Senate. In 1905, he was elected by the state legislature to fill the remainder of the full term for the US Senate seat (to 1909). [citation needed]

Knox made an unsuccessful bid for the Republican Party nomination in the 1908 U.S. presidential election.

U.S. Secretary of State

[edit]

In February 1909, President-elect William Howard Taft nominated Senator Knox to be Secretary of State.[9] He was at first found to be constitutionally ineligible, because Congress had increased the salary for the post during his Senate term, thus violating the Ineligibility Clause.[10] In particular, Knox had been elected to serve the term from March 4, 1905 to March 3, 1911. During debate on legislation approved on February 26, 1907, as well as debate beginning on March 4, 1908, he had consistently supported pay raises for the Cabinet, which were eventually instituted for the 1908 fiscal calendar.[10][11] The discovery of the constitutional complication came as a surprise after President-elect Taft had announced his intention to nominate Knox.[10]

The Senate Judiciary Committee proposed the remedy of resetting the salary to its pre-service level, and the Senate passed it unanimously on February 11, 1909.[11] Members of the U.S. House of Representatives mounted more opposition to the relief measure and defeated it once. After a special procedural rule was applied, the measure was passed by a 173–115 vote.[12] On March 4, 1909, the salary of the Secretary of State position was reverted from $12,000 to $8,000, and Knox took office on March 6.[10][11] Later known as the "Saxbe fix", such legislation has been passed in a number of similar circumstances.

Knox served as Secretary of State in Taft's cabinet until March 5, 1913. As Secretary of State, he reorganized the Department on a divisional basis, extended the merit system to the Diplomatic Service up to the grade of chief of mission, pursued a policy of encouraging and protecting American investments abroad, declared the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment, and accomplished the settlement of controversies related to activities in the Bering Sea and the North Atlantic fisheries.

Under Taft the focus of foreign policy was the encouragement and protection of U.S. investments abroad called Dollar diplomacy. This was first applied in 1909, in a failed attempt to help China assume ownership of the Manchurian railways.[13] Knox felt that not only was the goal of diplomacy to improve financial opportunities, but also to use private capital to further U.S. interests overseas. When the Zionist Literary Society sought endorsement from the Taft administration, Knox recommended against approval, noting in his assessment that "problems of Zionism involve certain matters primarily related to the interests of countries other than our own." [14] In spite of successes, "dollar diplomacy" failed to counteract economic instability and the tide of revolution in places like Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and China.[15]

Return to the Senate

[edit]

Following his term of office, Knox resumed the practice of law in Pittsburgh. In 1916, Knox was elected by popular vote to the Senate from Pennsylvania for the first time, after passage of the Seventeenth Amendment providing for such popular elections. He served from 1917 until his death in 1921. While a Senator, he was highly critical of the Treaty of Versailles ending World War I, saying "this Treaty does not spell peace but war — war more woeful and devastating than the one we have but now closed".[16]

At the 1920 Republican National Convention, Knox was considered a potential compromise candidate who could unite the progressive and conservative factions of the party. Many thought that California Senator Hiram Johnson would release his delegates to back his friend Knox, but Johnson never did. Warren G. Harding instead emerged as the compromise candidate, and Harding went on to win the 1920 election.[17] After the election, Knox urged President Harding to consider Andrew Mellon for the position of Secretary of the Treasury, and Mellon ultimately took the position.[18]

In April 1921, he introduced a Senate resolution to bring a formal end to American involvement in World War I. It was combined with a similar House resolution to create the Knox–Porter Resolution, signed by President Warren G. Harding on July 2.[19]

Personal life

[edit]Knox's nickname was "Sleepy Phil," as he was said to have dozed off during board meetings, or because he was cross-eyed.[20]

Knox was a member of the elite Duquesne Club in Pittsburgh.[citation needed][21]

-

Exterior of home of Senator Philander Knox, 1527 K Street, NW, Washington, DC

-

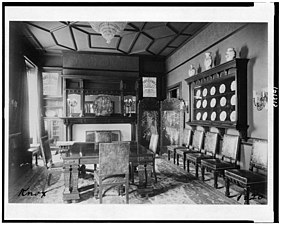

Office in Senator Philander Knox house in Washington, DC

-

Staircase in home of Senator Philander Knox

-

Dining hall in home of Senator Philander Knox

Death

[edit]Knox died in Washington, D.C., on October 12, 1921, aged 68.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Philander Chase Knox" (PDF). The New York Times. October 14, 1921.

- ^ Demmler, Ralph H (1977). "Knox & Reed; Reed, Smith, Shaw & Beal; Reed, Smith, Shaw & McClay", p. 7

- ^ Dodds, A. John (Mar–Jun 1950). "Philander C. Knox – Legal Adviser to Pittsburgh Business". The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. 33: 11–20.

- ^ Beveridge, Albert J. (1923). "Philander Chase Knox, American Lawyer, Patriot, Statesman". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 47 (2): 89–114. JSTOR 20086501.

- ^ a b Robert D. Christie (April 1971). "The Johnstown Flood". The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. 54 (2). Archived from the original on 2019-06-03. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ ""May 31, 1889 CE: Johnstown Flood", National Geographic. Retrieved June 3, 2019". Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Shugerman, Jed Handelsman (2000). "Note: The Floodgates of Strict Liability: Bursting Reservoirs and the Adoption of Fletcher v. Rylands in the Gilded Age". Yale Law Journal. 110 (2): 333–377. doi:10.2307/797576. JSTOR 797576.

- ^ Morris, Edmund (2001). Theodore Rex. New York: The Modern Library. p. 300. ISBN 0-8129-6600-7.

- ^ 43 Congressional Record 2390–403 (1909).

- ^ a b c d "Knox Seems Barred From the Cabinet". The New York Times. 1909-02-10. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ a b c "Knox Relief Bill Passes in Senate" (PDF). The New York Times. 1909-02-12. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ "Way Clear For Knox to Enter Cabinet" (PDF). The New York Times. 1909-02-16. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ For more on Knox's actions in Manchuria, see Michael H. Hunt, Frontier Defense and the Open Door: Manchuria in Chinese-American Relations, 1895–1911, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1973

- ^ Neff, Donald (1995). Fallen pillars: U.S. policy towards Palestine and Israel since 1945. Washington, D.C: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 978-0-88728-262-1.

- ^ "Dollar Diplomacy, 1909–1913". Office of the Historian, United States Department of State. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Harmony of the Secret Treaties and the 14 Points". Harper's Weekly. 2: 33. 1919. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ "Harding Nominated for President on the Tenth Ballot at Chicago; Coolidge Chosen for Vice President". The New York Times. 13 June 1920. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ Cannadine, David (2006). Mellon: An American Life. A. A. Knopf. pp. 525–526. ISBN 0-679-45032-7.

- ^ Staff (July 3, 1921). "Harding Ends War. Signs Peace Decree At Senator's Home. Thirty Persons Witness Momentous Act in Frelinghuysen Living Room at Raritan". The New York Times.

- ^ The Bookman. Vol. 23. Dodd, Mead and Company. 1906. p. 309.

- ^ Vondas, Jerry (July 23, 2006). "Pittsburgh Club Endures Almost 130 Years after Founding". Pittsburgh Tribune Review.

Further reading

[edit]- Coletta, Paolo E. The Presidency of William Howard Taft (1973).

- Coletta, Paolo E. “The Diplomacy of Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft.” In American Foreign Relations: A Historiographical Review, edited by Gerald K. Haines and Samuel J. Walker, (Greenwood Press, 1981) pp 91–114.

- Collin, Richard H. "Symbiosis vs. Hegemony: New Directions in the Foreign Relations Historiography of Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft." Diplomatic History 9#3 (1995), 473–497.

- Gould, Lewis L. The William Howard Taft Presidency (UP of Kansas 2009) excerpt

- Holsinger, M. Paul. "Philander C. Knox and the Crusade against Moromonism, 1904–1907." Western Pennsylvania History (1969): 47–55. online

- Mulhollan, Paige Elliott. "Philander C. Knox and Dollar Diplomacy, 1909–1913" (PhD dissertation The University of Texas at Austin, 1966.); online at ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Scholes, Walter V., and Marie V. Scholes. The Foreign Policies of the Taft Administration (1970). online

External links

[edit]- Letters from and to Secretary of State Knox, Ursinus College Archives

- United States Congress. "Philander C. Knox (id: K000296)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- 1853 births

- 1921 deaths

- People from Brownsville, Pennsylvania

- Candidates in the 1908 United States presidential election

- Candidates in the 1920 United States presidential election

- United States secretaries of state

- Attorneys general of the United States

- Politicians from Pittsburgh

- University of Mount Union alumni

- Pennsylvania Republicans

- Republican Party United States senators from Pennsylvania

- West Virginia University College of Law alumni

- Taft administration cabinet members

- Theodore Roosevelt administration cabinet members

- McKinley administration cabinet members

- 19th-century American politicians

- 20th-century United States senators